Spatial Biology: A New Frontier in Understanding Biological Systems

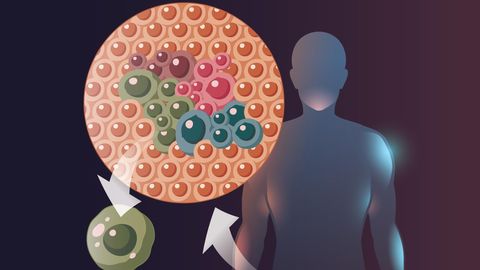

Spatial biology is unlocking a new dimension in biomedical research, revealing how the organization of cells and molecules drives health and disease.

Tissue function is shaped by a complex, multilayered molecular landscape, where even subtle disruptions in spatial organization can trigger – or indicate – the onset of disease.

“Spatial biology allows you to map the cellular organization and molecular interactions that happen directly in the tissue microenvironment,” explained Ines Sequeira, associate professor in oral and skin biology and deputy director of research at Queen Mary University of London. “By doing so, you can begin to truly understand how biological systems work in their spatial context.”

By capturing the spatial distribution of biomolecules – such as DNA, RNA, proteins and metabolites – these approaches can reveal disease-associated molecular signatures, cell states and multicellular niches, as well as how the tissue microenvironment shapes disease progression.

“You can now look at tissues in a way that pathologists simply couldn’t for the past 160 years,” said Nikolaus Rajewsky, scientific director of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology and professor of systems biology at the Max Delbrück Center. “It opens a window into how cells communicate and respond to challenges, giving us the chance to understand the molecular mechanisms that drive phenotypes.”

Today, researchers are using spatially resolved methods to explore diverse biological processes – from development and tumorigenesis to fibrosis, neurodegeneration, infection and inflammation – offering unprecedented new insights into health and disease.

Spatial biology tools

Over the past decade, single-cell omics has dramatically broadened the scope of molecular profiling, capturing genomes, epigenomes, metabolomes and transcriptomes at single-cell resolution. These methods revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity, uncovering rare cell types and diverse phenotypic states. However, as Sequeira pointed out, “these single-cell technologies rely on dissociating the tissue and destroying its three-dimensional architecture.”

A new generation of high-throughput spatial omics is now bridging this gap, combining the depth of single-cell profiling with the anatomical context of intact tissues. These technologies deliver highly multiplexed molecular data in situ, allowing researchers to study biological processes within their native tissue environment in unprecedented detail.

“We’re now in an era of molecular digitalization – you can really count molecules in cells inside the tissue,” said Rajewsky. “Transcriptomics is the most prominent example, providing exact XYZ coordinates for RNA molecules in their native environment.”

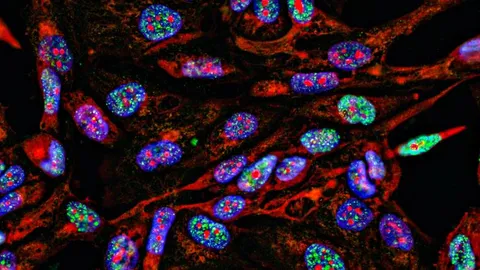

Sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics platforms, such as Stereo-seq, can capture entire transcriptomes at subcellular resolution, while imaging-based methods, such as MERFISH and seqFISH+, can count and localize thousands of RNA molecules within individual cells. Resolution can be further enhanced with techniques like expansion microscopy, which physically enlarges tissue samples to separate densely packed molecules.

Spatial proteomics is also advancing rapidly. Techniques such as imaging mass cytometry (IMC), cyclic immunofluorescence (cycIF), CODEX, IBEX and MIBI generate highly multiplexed images of protein composition and spatial organization within tissues. “Spatial proteomics is more challenging,” noted Rajewsky, “but has also made tremendous progress. You can now quantify a few thousand proteins from a few cells spatially in a tissue, which is really fantastic.”

The field is also extending into spatial metabolomics, where mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) techniques can chart the distribution of small molecules – such as metabolites, lipids or drugs – at near single-cell resolution. These approaches provide spatially resolved metabolic maps, revealing novel insights into networks and alterations underpinning health and disease.

“It’s a field that is evolving at incredible speed,” said Sequeira. “Keeping pace with the technologies – and also the computational tools for analysis – is a challenge in itself.”

Powering discovery

The impact of spatial biology is already being felt across many different areas of biomedical research.

“There’s been a huge boom of applications,” says Sequeira. “A lot of these technologies were originally developed for studying the brain, but their use has expanded enormously into many other fields.”

In cancer research, spatial biology tools are illuminating the tumor microenvironment, mapping how cancer cells interact with immune and stromal populations, and uncovering mechanisms of immune evasion. They are also being used to dissect tumor heterogeneity, providing critical insights for precision oncology and informing the development of new targeted therapies.

In neuroscience, spatial transcriptomics and proteomics are providing unprecedented views of brain organization, from developmental patterning to the molecular changes underlying neurodegenerative diseases. Similarly, in developmental biology, spatial methods are shedding light on how cells communicate, specialize and organize to form tissues and organs.

Researchers are also applying spatial techniques to study diverse biological processes – such as fibrosis, infection and inflammation – to uncover how tissue remodelling and immune responses are orchestrated with the tissue microenvironment. For example, Sequeira is investigating wound healing in the oral mucosa. “We’re using spatial biology to map cellular interactions and uncover signals during oral wound healing,” she explained. “Our goal is to understand what makes the oral mucosa unique – a tissue that heals exceptionally fast and without scarring compared to skin.”

Overcoming spatial biology challenges

Despite its transformative promise, spatial biology faces several key hurdles before its full potential can be realized.

A major challenge is data integration. Different spatial platforms often lack standardization and interoperability, making it difficult to compare results across studies or combine different molecular readouts.

“You might have someone producing fantastic spatial proteomics data – but if you can’t connect it to other readouts or cellular variables, it remains isolated,” said Rajewsky. “You don’t get to solve the mysteries of how cells make decisions – that’s why finding ways to integrate these different datasets is so key."

Data management and analysis present another significant barrier. Spatial biology generates vast, highly complex datasets – often many terabytes – that can quickly strain storage and computational infrastructure. “We’re excellent at generating Big Data, but analyzing it has become a bottleneck,” noted Sequeira. “To truly leverage these datasets, you need a dedicated team of computational biologists.”

Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful tool to help tackle the analytical challenge. AI-driven approaches can sift through spatial datasets to uncover patterns, reveal underlying biological mechanisms and accelerate biomarker discovery. “AI excels at connecting the dots between different data types,” said Rajewsky. “In many ways, it’s becoming the pathologist of the future.”

Accessibility and cost remain additional obstacles, as many spatial biology platforms are prohibitively expensive. To address this, Rajewsky’s team recently launched Open-ST, an open-source spatial transcriptomics resource providing experimental protocols and computational tools for analyzing tissue molecular organization in 3D at subcellular resolution. By improving cost-efficiency and scalability, Open-ST enables researchers to map cell types and their spatial relationships within tissues, such as mouse brains and tumors, revealing new insights into biological processes and disease mechanisms.

“The goal is to democratize spatial transcriptomics,” explained Rajewsky. “It doesn’t require specialized equipment, it’s far more affordable than commercial platforms, and it’s very robust and precise.”

The future of spatial biology

As spatial biology continues to advance, researchers have access to an ever-expanding toolkit for exploring the molecular architecture of tissues. When combined with AI-driven analytics, these tools are opening exciting new avenues to understand tissue function in health and disease.

“We’re trying to understand this microscopic world within us, down to the cellular and molecular level,” said Sequeira.

By uncovering the spatial organization of cells, their interactions and the molecular underpinnings of disease, the field is poised to transform both biomedical research and medicine.

“I believe the impact will be profound,” concluded Rajewsky. “These advances will change how we approach pathology, identify drug targets – and ultimately, how we prevent and treat diseases through precision medicine.”