Expert Perspectives on Spatial Transcriptomics

eBook

Published: December 8, 2025

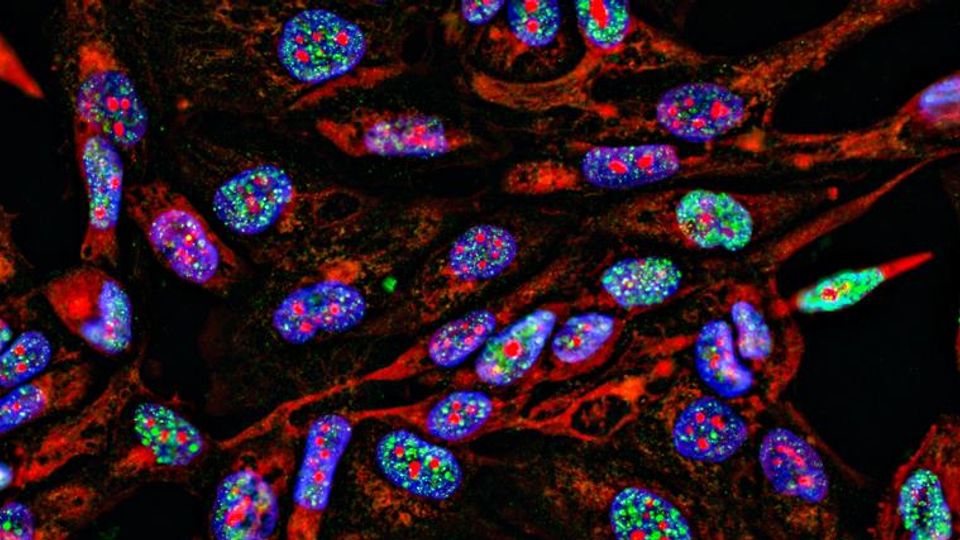

Credit: iStock

In multicellular organisms, each cell is influenced by the others in its surrounding environment, and the maintenance of cellular and tissue spatiality – or lack thereof – carries significant implications for everything from Alzheimer’s disease and cancer to autoimmune conditions.

Spatial biology provides unprecedented insights into this organization by shedding light on global cell-type organization, cell–cell interactions, disease biomarkers and more.

This eBook introduces you to six researchers who have adopted spatial transcriptomics in their fields of oncology, immunology and neuroscience. They share how taking a spatial approach has allowed them to make incredible breakthroughs.

Download this eBook to explore:

- Advice for researchers getting started with spatial transcriptomics

- Considerations for choosing a spatial platform

- How spatial omics is shaping the future of therapeutics

eBook

Perspectives

from Global Pioneers

in Spatial

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 2

Charting biology:

The case for spatial transcriptomics

In multicellular organisms, no single cell exists in a

vacuum. Each cell is influenced by the others in its

surrounding environment, the signals that pass

between them determining their functions.

In fact, the maintenance of cellular and tissue

spatiality—or lack thereof—carries significant

implications for everything from Alzheimer’s disease

and cancer to autoimmune conditions and immune

responses to infection.

Spatial biology provides unprecedented insights into

this organization by shedding light on global cell-type

organization, cell–cell interactions, heterogeneous

spatial niches, novel gene programs, critical ligand–

receptor signaling networks, and biomarkers associated

with disease.

Examining biological molecules within appropriate

morphological context has been possible since the

1940s. While early publications for

immunohistochemistry1 and in situ hybridization2,3

proved spatial profiling was possible, they were limited

in the number of detectable targets and resolution.

Today, we can map hundreds of transcripts up to the

whole transcriptome4–7 while achieving single cell or

even subcellular resolution.

Spatial transcriptomic technologies can be divided into

two primary categories: imaging-based and sequencingbased.

Imaging-based techniques, such as Xenium

Spatial assays, label and image transcripts directly

within a tissue slice. Sequencing-based techniques,

such as Visium Spatial assays, release and capture

transcripts or ligation products corresponding to

transcripts from tissues and then analyze those

products using an external sequencer.

Which method is right for you, ultimately, depends on

your specific experimental questions and/or needs.

This eBook introduces you to six researchers at the

forefront of adopting spatial biology in their fields of

oncology, immunology, and neuroscience. They share

how taking a spatial approach has allowed them to make

incredible breakthroughs, discuss what they considered

when choosing a spatial platform, and give advice to

researchers starting to explore spatial transcriptomics.

“Architecture is what ultimately

distinguishes a living cell from a

soup of the chemicals of which it

is composed. How cells generate,

maintain, and reproduce their

spatial organization is central to

any understanding of the living

state.”

Whellan DJ and O’Connor CM. Function follows

form. JACC Heart Fail 9: 482–483 (2021). doi:

10.1016/j.jchf.2021.02.012

FPO

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 3

Table of contents

Mapping immunity:

Dr. Reina-Campos discusses the power of spatial transcriptomics 04

From allergies to autoimmunity:

Dr. Poholek’s guide to cutting-edge spatial research 08

Spatial biology at scale:

Dr. Banovich on decoding disease with a new dimension of context 13

Defining tumor boundaries:

Dr. Ye’s spatial exploration of immune escape mechanisms 17

Shaping future therapeutic possibilities:

Dr. Freytag on the power of spatial insights in clinical research 20

Unveiling tumor secrets:

Dr. Watson’s spatial multiomics approach to glioblastoma research 26

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 4

Miguel Reina-Campos, PhD

Assistant Professor

La Jolla Institute for Immunology

Mapping immunity:

Dr. Reina-Campos discusses the

power of spatial transcriptomics

Tell us about why spatial transcriptomics is so important for the research that

you do.

Absolutely. For decades, immunologists have been studying how the different pieces

of the immune system work. They’ve looked at these pieces using many different

technologies and applications. We understand a great deal about how these different

pieces work, their diversity, and how they function, but much less is known about the

specifics of where those species have to operate in tissues. It has always been a

Dr. Reina-Campos’ research

focuses on specialized

immune cells called tissueresident

T cells that live

deep within our organs,

such as the colon or the

liver, to provide fast and

robust protection against

future infections and

tumors. In particular, his lab

is interested in unlocking

the mechanisms that make

tissue-resident T cells

proficient at their jobs in

hopes of revealing new

approaches to revamp

the immune response

against cancer.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 5

mystery to really observe those immune cells within

their natural environments.

My lab is studying how to better leverage the immune

system that exists within tissues. Funnily enough, we

had never been able to observe those cells in the tissues

they are protecting. Prior to spatial transcriptomics, our

observations had always been very indirect. We either

had to make smoothies out of the tissues to separate the

cells to study them, but obviously losing their natural

environment, or we would do histological stains but at a

very low plex of maybe 3–5 markers. However, that in

itself is not enough to understand the very rich

ecosystem these cells live in.

We also study the differentiation of the immune system,

which means looking at what genes the immune cells

are expressing and when they are expressing them. We

have been using single cell technologies like scRNA-seq

to look at their RNAs, proteomics to look at their

proteins, and even metabolomics to look at the

metabolites. But, we had never been able to put the two

things together—where these cells are in a tissue and

what they are expressing. With spatial transcriptomics,

for the first time, we were able to observe our favorite

immune cells in unperturbed, natural environments at

a resolution that we had never been able to look at before

and at a plex that we had never even dreamed of before.

These spatial transcriptomics technologies, I know lots

of folks are very interested in them, but for us, they

came as a necessity. We needed this technology to get to

the answers that we were looking for.

Do you have some specific examples of how spatial

has impacted the line of research that you’re

looking at?

The cells that we study are mighty and powerful, but

they are not very abundant. We needed something that

would enable us to look at those small lymphocytes,

sometimes located next to bigger and much more

abundant tissue cells, and see what they express. Using

Xenium technology has enabled lots of cool research

coming out of our lab, and other labs, in defining the

The image depicts three overlapping layers of biological information in the mouse small intestine—protein (left), to cell types (middle), to individual transcripts (right)—offering a new

window into the secret life of tissue-resident memory T cells (purple, right).

Image credit: Reina-Campos lab.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 6

spatial patterning of how the immune system is

interconnected within a tissue architecture.

For example, we’ve looked at the small intestine and

found that these immune cells, which come in different

flavors—some are more effectors while some are more

progenitors—are actually localized in different parts of

the intestine. This spatial distinction of immune

subtypes is something that we had never been able to

look at before. Not only that, because we have spatial

context, we can now understand what signals are

driving that heterogeneity and better understand how

tissue–immune networks happen in the context of

infection and tumors.

You talked about needing to see cells that weren’t

very abundant. What other considerations did you

take into account when you were choosing what

type of spatial you were going to pursue?

At the beginning, when these new technologies came

along and there were different emerging players in the

field of spatial transcriptomics, we were technology

agnostic as long as we could get to the bottom of our

research. We just wanted to get good data and by that I

mean getting the maximum sensitivity and the

maximum surface area for the maximum amount of

transcripts that we could.

But then we realized that having robust technology is

pretty important and were disappointed with other

platforms. When we started using 10x Xenium,

something that we really liked was that it was very

robust. It was an almost end-to-end solution where you

could have your tissues, start in a prep, and then end up

looking at your data a couple of weeks later, already

getting some insights into your problem. Other

technologies did not have that end-to-end solution yet.

We appreciated having that already built in. Nowadays,

being reproducible and robust is a big deal for us.

Another consideration was that it works with formalinfixed

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples. I think that’s

what most people have access to, and it unlocks

thousands of samples coming from clinical practice.

Other technologies struggled with FFPE, and we

understood the chemistry that 10x was providing could

work very reliably with FFPE.

So, robustness and FFPE compatibility were the two

considerations that were defining for us in choosing 10x

over others. I ultimately think having multiple options

will be best for us researchers.

“With spatial transcriptomics,

for the first time, we were able

to observe our favorite immune

cells in unperturbed, natural

environments at a resolution that

we had never been able to look at

before and at a plex that we had

never even dreamed of before.”

Spilling the (immune) secrets of our guts

Our intestines play a crucial role in providing

protection from infections thanks in part to the

presence of tissue-resident memory CD8 T (TRM)

cells. To understand the two different types of TRM

cells present in the intestines and how their location

impacts the role they play, Reina-Campos et al.

harnessed the high resolution of Xenium single cell

spatial imaging and the whole transcriptome

profiling power of Visium sequencing-based spatial

transcriptomics. This powerful approach, alongside

a novel spatial CRISPR knockout experiment,

revealed how fundamentally connected a T cell’s

location is to dictating its functional state.

Read the publication to discover what cellular

secrets were revealed >

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 7

A lot of people see the promise of spatial biology,

but may be hesitant to jump into a new technology.

What advice would you give for people who are just

starting out in spatial to help them be successful?

I think you kind of have to address the elephant in the

room, which is the price. People who get stuck on the

price without looking at the data often change their

minds once they see the data and all the information

that can be unlocked. My advice is to run one pilot

experiment to see the data, so you can really appreciate

what it can do for your project.

But still, price remains a challenge and a gatekeeper for

many. So moving forward, we should aim to encourage

companies to have a lower level of entry and

democratize this technology so more people can use it,

because it really is an amazing technology. It’s my hope

that very soon it will cost a tenth of the price so more

people can use it.

Are there any new directions or capabilities within

the field of spatial biology and spatial technologies

that you would be really excited to see pop up in

the future?

Absolutely. One of the considerations for choosing 10x

Xenium over other technologies is its non-destructive

approach to spatial transcriptomics. Meaning that when

you’re done with your experiment, you still have your

tissue mostly intact, which enables you to pair it with

multiomic readouts. Having 5,000 genes and up to a

couple dozen protein stains you can maybe look at after

your experiment, that’s one thing. Other omics

modalities like metabolomics would be very powerful.

I anticipate people will want to know all the genes, but

the downside is sensitivity challenges at higher plexy.

I’m hoping in the future we get that right balance of

higher sensitivity and higher plex.

Is there anything else you want to highlight, a

particular publication from your lab, or any other

thoughts you want to share on spatial?

Spatial transcriptomics requires a blend of expertise

that no single person can possibly have. I was super

lucky to be part of a team, first with a fantastic mentor

that enabled this research. I’ve had amazing colleagues

supporting different aspects of our projects, all of which

are required for the spatial transcriptomics to succeed.

From the bioinformatics to the sample preparation to

the histology to the in vivo animal experiments, you

really need a 2–4 person team to do any of these big

experiments. I want to acknowledge that it’s not a oneman

show. These are complex experiments that require

full teams.

Because of the work of our team, we were able to find

that the heterogeneity of the immune system is spatially

imprinted, at least in the gut, and we suspect in many

other tissues as well. Those findings were accepted for

publication three weeks ago and will soon be published

in Nature. We’re very excited that more and more people

are going to be using this. I can’t wait to see where it

leads us.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 8

From allergies to autoimmunity:

Dr. Poholek’s guide to cutting-edge

spatial research

What was your introduction to spatial transcriptomics, and why did you decide

that it would be necessary for your research?

First, I’m the director of the Health Sciences Sequencing Core at the University of

Pittsburgh, which provides Next Generation Sequencing services for the institution.

We are always looking at new technologies in the sequencing space that we think

might be in demand for researchers at the university and to make sure that we’re able

to offer cutting-edge approaches to answer their research questions.

Amanda Poholek, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Immunology

Director, Health Sciences Sequencing Core

University of Pittsburgh

Dr. Poholek is an assistant

professor at the University

of Pittsburgh. Her lab aims

to understand how immune

cells sense different signals

and tissue environments to

decide what kind of cells

they need to become. Of

particular interest is cell

response to signals that

should cause activation but,

due to failure to tolerate

non-harmful stimuli, lead

to autoimmune and allergic

diseases. Additionally,

Dr. Poholek serves as the

Director of the Health

Sciences Sequencing Core.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 9

In my own research, we had an unexpected finding that

the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 was required for

the differentiation of T helper 2 (Th2) immune cells

specifically in the lung. These are the cells that can

drive the physiologic symptoms of allergic asthma, such

as mucus production, airway hyperresponsiveness, and

smooth muscle constriction. Prior to our work, although

we knew a lot of the factors critical for the development

of Th2 cells, we hadn’t appreciated that Blimp-1 was

required for that process. It was really a surprise

because other work in other systems where Th2 cells

develop, such as responses to worm antigens, had not

demonstrated that Blimp was important for promoting

an effective response but, rather, for constraining an

effective response.

Based on these disparate functions of Blimp-1 in

different contexts, we decided to directly test if the

route by which you experience the allergen actually

drives a difference in the genetic pathways that you

need to form these pathogenic Th2 cells driving allergic

asthma. And it turned out that there was a difference.

If you intranasally administer an allergen to an animal,

then you need Blimp-1 to become a Th2 cell. However, if

you administer the same allergen subcutaneously or

systemically, you can form Th2 cells without needing

Blimp-1 at all.

These data really suggested that there was a tissuespecific

pathway through the lung, driving an effector

T-cell response that we had not previously understood. I

H&E VisiumHD

H&E overlay 8μm bins

Visium data from mediastinal lymph node three days following house dust mite exposure. H&E stain (left) and graph-based clustering of FFPE Visium HD (right). Inset shows a HEV by

H&E (left), overlay with transcriptional clustering (middle) and 8-μm spatial bins (right) for analysis.

Image credit: Poholek lab.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 10

wanted to understand this at the initiation of the

response to better understand how a naïve T cell

interprets the information it receives during activation

in the context of the tissue that experiences the antigen.

Since the lymph node is the place where the T cells

typically see antigen for the first time, we wondered if,

by looking at the same exact response to the same exact

antigen in lymph nodes draining two different tissue

sites, we would reveal information about the pathways

and spatial niches needed for those immune cells to

become the effector cells that drive allergic asthma.

I proposed in a grant to use spatial transcriptomics as

an unbiased mechanism to examine these two different

lymph nodes, draining either the skin or the lung. When

you look at the initiation of the immune response to an

allergen, how do those two sites differ?

We are still working to answer this question but it’s what

got us interested in spatial transcriptomics as a

technology. While setting up these systems, we made an

observation in the lung-draining lymph node that was

so striking to us that we paused there and dived in. This

work was published in Nature Immunology recently,

where we identified spatial microniches of the cytokine

IL-2 that were important for the formation of Th2 cells

in allergic asthma through Blimp-1.

We used spatial transcriptomics to identify Th2 cells in

the lymph node, and then applied a new algorithm

developed by our very talented collaborator, Dr. Jishnu

Das, called SLIDE, which stands for Significant Latent

Factor Interaction Discovery and Exploration. SLIDE

can identify latent factors or hidden variables in highdimensional

datasets that underlie specific observable

features. Dr. Das was eager to use SLIDE on a spatial

dataset, and our localization of Th2 cells in the lymph

node provided an ideal opportunity. SLIDE identified

IL-2Ra in a significant latent factor that was supporting

differences in the localization of Th2 cells in the lymph

node. Then, we were able to validate that IL-2 was acting

as a local microniche in the lymph node to promote

initiation of Blimp-1 to drive Th2 cells using other

methods. I think our example of how we got into spatial

transcriptomics is very typical—you have a biological

question that requires spatial tissue context but also

highlights the need for new computational approaches

that can reveal biological insight.

There are different flavors of spatial transcriptomics

these days, imaging-based and then NGS-based

systems. Which type are you using for your work,

and what considerations did you take into account

when deciding for your specific project?

Currently, we’re using both. We started with NGS-based

because those were the ones that were commercially

available. Specifically, we used the 10x Genomics

Visium Spatial Gene Expression and Curio Biosciences

Seeker™ platforms, and that’s what we used in our recent

publication. We’re now working with both the Visium

and imaging-based Xenium platforms.

There are several important considerations when

thinking about these two different flavors. Now that we

have higher resolution with Visium HD, the sequencingbased

applications offer truly unbiased approaches at

the single cell level and the ability to stain the same

tissue section for imaging that you use for spatial

transcriptomics. I think there’s some real power there if

you aren’t 100% sure what you’re looking for, so it’s

really useful in a discovery setting.

Imaging-based platforms are also incredibly powerful at

the single cell level. And now that they have probe sets

that have gotten up to 5,000–6,000, you can do a lot of

discovery-based work there, too. However,

“I think our example of how we

got into spatial transcriptomics

is very typical—you have a

biological question that requires

spatial tissue context but also

highlights the need for new

computational approaches that

can reveal biological insight.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 11

imaging-based platforms are more beneficial if you have

a really targeted set of genes you’re interested in. You

can do more high-throughput studies, get more tissue

into a run, and get a lot more information at a broader

scale. Whereas for sequencing-based platforms, you get

more information at the single cell level from the whole

transcriptome but are limited in the amount of tissue

that you can look at per run.

As a core director, what advice do you give to

people looking to get started in spatial but are

unsure where to begin?

The first piece of advice I’d give is the same for any

sequencing application: ask yourself what biological

question you’re trying to answer and then use the

platforms or technologies that are the most appropriate

to your question.

Having a sense of what you’re hoping to find is really

important when approaching any of these technologies.

The second piece of advice is to really know your tissue.

Our experience running a core and offering this as a

service has allowed us to run over 30 projects and easily

more than a dozen different tissues in mouse and

human. Every tissue is different, and there are critical

considerations when dealing with different tissue types.

I advise talking to someone with broad expertise across

multiple tissues if available at your institution. If not,

take the time to do pilot runs with your tissue to make

sure that it adheres the way you expect it to, that it

stains the way that you expect it to, and that you’re able

to get good quality sequencing data out of your tissue.

We always do QC to know the RNA quality of our tissues

before we proceed. If the quality of the RNA is not high,

the returns are quite diminishing.

It’s worth the effort to source and have very good quality

material. If it’s material that’s easy for you to get, like

from a mouse study, make every effort to collect that

tissue with spatial in mind. You’re better off generating

a new tissue block where you’ve thought clearly about

RNA integrity rather than digging through the –80°C

freezer to find something.

Thinking into the future, what new directions or

capabilities would you be particularly excited to see

emerge in the arena of spatial biology?

We get asked by many people how much protein

staining can be done. Of course, people can do

immunofluorescence, but it’s somewhat limiting. I

think some of the barcoded antibody protein panels that

could be offered commercially to go along with some of

these platforms would be very useful for many projects.

Along those same lines, I’m excited about adding

additional modalities where you can do not just gene

transcription but also protein and potentially mass

spectrometry to look at metabolites or adding in

epigenetics. Really, multimodal spatial is something

that I’m excited to see come out.

The other thing that we’ve done a little bit of, but, again,

would be heavily utilized if more commercially

available, would be spatial TCR and BCR sequencing for

those of us in the immune space.

“The first piece of advice I’d give

is the same for any sequencing

application: ask yourself what

biological question you’re trying

to answer and then use the

platforms or technologies that

are the most appropriate to

your question.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 12

Is there anything else you’d like to

cover or highlight?

Yes. As I mentioned when describing our recent findings

in allergic asthma, it is important to highlight the need

for innovative computational methods for the spatial

space. We saw this a lot with single cell early on, where

there was a lot of effort working to properly analyze and

visualize single cell datasets.

We’re in that same area right now for spatial. I think

people are utilizing the single cell algorithms,

sometimes effectively, but sometimes less effectively,

for spatial.

What we absolutely need, and we’re seeing this from

some groups, are gold standard computational

approaches for spatial that will win out in terms of their

utility—approaches thinking about the data as spatial

data rather than just trying to co-opt single cell

algorithms into spatial algorithms. That’s an area for

tremendous development that will also allow us to gain

the most biological insight from these amazing new

technologies in spatial transcriptomics.

“What we absolutely need, and

we’re seeing this from some

groups, are gold standard

computational approaches for

spatial that will win out in terms

of their utility—approaches

thinking about the data as spatial

data rather than just trying to

co-opt single cell algorithms into

spatial algorithms. That’s an area

for tremendous development

that will also allow us to gain

the most biological insight from

these amazing new technologies

in spatial transcriptomics.”

Inhaled, mapped, understood:

Spatial microniches driving allergic asthma

Our immune systems respond to lots of antigens, sometimes in very different tissue environments. Compelled

to understand lung-specific responses to inhaled allergens—given that asthma is one of the most common and

most costly diseases—He et al. combined Visium Spatial Gene Expression data with immunofluorescence to

map the molecular pathways activated over time. This approach highlighted the unexpected but important role

interleukin 2–mediated spatial microniches within the lung draining lymph node play in allergic asthma.

Dive into these findings featured in Nature Immunology >

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 13

Nicholas Banovich, PhD

Director of the Center for Spatial Multi-Omics

The Translational Genomics Research Institute

(TGen), part of City of Hope

Dr. Banovich’s research

group leverages advanced

genomic technologies,

such as single cell RNA

sequencing and spatial

transcriptomics, to

understand how genetic

and molecular variations

contribute to disease. This

work aims to identify new

biomarkers and therapeutic

targets to improve patient

outcomes across multiple

disease areas, including

chronic lung disease

and cancer.

Spatial biology at scale:

Dr. Banovich on decoding disease

with a new dimension of context

Can you describe your research and your lab at TGen?

My primary function is running a research lab. We are focused on understanding how

gene regulatory changes impact disease outcomes—whether that’s initiation,

treatment response, or disease progression.

One of our major projects is focused on pulmonary fibrosis (PF). We also focus on

correlative analyses from patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapies for brain tumors.

So we use very different biological systems, but they’re unified by the set of tools

and approaches.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 14

Behind the breath: Spatial insights into lung remodeling and PF

According to the Pulmonary Fibrosis Research Foundation, each year

approximately 50,000 new cases of PF will be diagnosed. Vannan et al. used

Xenium single cell spatial imaging to map the structural and cellular changes that

are a hallmark of idiopathic PF. This spatial gene expression of 1.6 million cells

from 35 unique lungs allowed the team to explore the progressive remodeling of

distinct spatial niches throughout the course of PF disease progression.

Check out this groundbreaking research that earned a cover feature in

Nature Genetics >

We’ve built a foundation on single cell transcriptomics

and using the single cell information to understand

molecular dysregulation and disease at cell-type

resolution. Over the past couple of years, we’ve started

to put more of a focus on spatial technologies, and we’ve

been using Xenium since February of 2023.

My other role at TGen is operating and directing the

Center for Spatial Multi-Omics (COSMO) technology

core. At the core, we offer both Xenium and Visium HD

assays as a service to internal TGen investigators and

external researchers as well.

Can you tell us more about how spatial has

impacted your research projects?

We think about the same types of questions that we

thought about with single cell approaches, but spatial

data has a lot of added benefits. It gives us

understanding not just of the cell type–level

dysregulation, but also the organization of cells into

architectural niches. We can start asking: what types of

cells are grouping together as disease progresses or in

response to treatment? Do we see more local or broader

changes in both the cell-type and molecular

composition of tissues?

Another really important benefit is not having to put

your tissue sample through a dissociation procedure.

For example, when dealing with the lung, there are a lot

of really fragile cell types, which has its challenges for

single cell experiments. In the alveoli—the little air sacs

that fill up with air and move oxygen out of the air into

your blood—there are two key cell types: alveolar type I

(AT1) epithelial cells and capillary cells.

The AT1 cells touch the air, and the capillary cells sit up

against the AT1 cells. They’re both very thin and really

integrated across the alveolus in three-dimensional

space. Because of that, we’re prone to lose those with

single cell approaches since they don’t survive the

dissociation process.

Some of these key cell types for understanding lung

biology tend to be underrepresented in our single cell

assays, but they perform quite well in the spatial data

because we don’t have to go through that tissue

dissociation step.

When you started exploring spatial technologies,

what did you take into consideration before

choosing the right one for your lab?

There were certainly spatial platforms out pre-Xenium,

but none of them offered single cell resolution. Because

of the complexity of the tissues we’re dealing with,

particularly the complexity of the lung, we need that

granularity to truly understand the biology. When we

could look at the spatial component and really have that

cell-type resolution, this is when spatial platforms

became exciting to me.

One of the things we really liked about Xenium, as we

were looking at the available offerings, was that a lot of

our tissues are formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

(FFPE) tissue, and Xenium has the ability to capture

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 15

transcripts even from fairly old, degraded FFPE

samples. These are samples that people collected, never

with the intention of using them for a molecular assay.

An anecdote that I like to share is that the oldest sample

we’ve profiled was about 15 years old. It had just sat on

my collaborator’s desk in a shoebox that he touched and

dug through with bare hands over the course of those

years—everything that just makes us, as RNA people,

die on the inside, you know? Except, we were still able to

get good data from it [with Xenium].

The high throughput of the Xenium system was also a

key factor because we were really excited about the

FFPE samples being amenable to tissue microarray

(TMA) approaches. That we could have almost 5 cm2 of

area per run started to help us envision how we might be

able to do these spatial projects at scale. What I mean is,

instead of just ten or fifteen samples, we could start

thinking about hundreds of samples that we

could process.

Switching to your core director role, how do you

explain spatial to new users?

There are two user groups that we deal with. One is

people already doing single cell who want to move to

spatial. For them, it is really about highlighting that we

still get that sort of single cell resolution, but with

spatial context.

The other user group we have are researchers who

haven’t really been involved with single cell approaches.

They may have done some sort of RNA in situ

hybridization in the past. Here we really talk about this

as a platform that allows you to take RNA in situ

hybridization and multiplex this across hundreds or

thousands of targets instead of just 1–4 targets. And,

actually, I think in some ways spatial data is more

intuitive for users who haven’t been doing genomics

than single cell data is. This is because you can provide

the files for the 10x Xenium Explorer, and people can go

on and look at it like you would an

immunohistochemistry experiment.

You can click on and off the genes that you care about,

and it’s very visually simple to understand that this blue

dot corresponds to the gene I care about.

Is there any advice you have for people who are just

getting started with spatial?

There are complexities on both the front end and the

back end that affect new users.

It certainly affected us as we started dealing with these

platforms. We didn’t have histology experience before

we started doing spatial transcriptomics. We were very

comfortable with traditional genomics workflows like

library prep and PCR. Tissue embedding, sectioning,

and staining were all things we had to learn.

So, if you’re coming from a genomics lab, there is a

learning curve to how you process tissues. It’s important

to either build those skills within your group, outsource

to a core, or work with a histology group that has

this experience.

On the other hand, there is a ton of complexity around

data analysis, and some of it is just a sheer numbers

problem. Our first two Xenium runs far surpassed the

number of cells we analyzed for the entirety of the

Human Cell Atlas work for the lung. We went from

“An anecdote that I like to share

is that the oldest sample we’ve

profiled was about 15 years old. It

had just sat on my collaborator’s

desk in a shoebox that he

touched and dug through with

bare hands over the course of

those years—everything that just

makes us, as RNA people, die on

the inside, you know? Except, we

were still able to get good data

from it [with Xenium].”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 16

thinking about datasets that have a 2–4 million cell cap

to a 60 million cell dataset. Ultimately, we had to move

the analyses over to GPUs to handle the processing.

The rest of the challenges, I think, are the fun

challenges like: how do we really utilize this relational

information? How do we link this to things we’re seeing

in the histology images?

How do you see spatial evolving, either in your

research or for the wider field in general?

This is a great platform, and I suspect this will become a

commodity over the next couple of years. As

development continues at 10x, we want to continue to be

able to provide services around the newest technologies.

We’re willing to go in and push on these technologies

and figure out what works well and doesn’t work well.

Then we want to share that knowledge with the

community, so that our early mistakes and triumphs

guide new users as they’re starting to set up.

As people get better and better at using Xenium, the

things we are doing now as front-edge users, like the

large-scale TMA analyses, will probably be easily done

by more researchers.

I envision, and hope, that we’ll be helping to spearhead

additional spatial applications on the horizon.

Is there anything that’s really cool or interesting

that you want to tell us about that you haven’t

gotten a chance to?

I think we’ve covered it! There’s all sorts of cool biology

we’re looking at, but every person’s cool biology is going

to be different, right? So the most exciting thing to me is

to have more people thinking about these studies with

bigger populations and really digging into their own

biological questions with this kind of new dimension

of information.

Tissue sample showcasing the diverse histopathology of the PF lung (H&E stain; leftmost panel), including an airway, multiple blood vessels, remodeled epithelium, and fibrosis. A

custom Xenium panel was used to profile 343 genes (second panel in). Individual nuclei and cells were viewed using DAPI and cellbound stains (third panel in). Individual features of

interest were extracted using FICTURE (bottom right; Si et al., 2024 Nature Methods). This is part of a set of 45 lung samples profiled in Vannan, Lyu et al. (2025) in Nature Genetics;

raw data available at Gene Expression Omnibus under accession GSE276945.

Image credit: Annika Vannan, Arianna Williams-Katek, Nicholas Banovich.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 17

Defining tumor boundaries:

Dr. Ye’s spatial exploration of

immune escape mechanisms

Tell us about your lab’s research focus.

Using single cell and spatial omics data as the foundation of our analyses, we

integrate innovative bioinformatics methods, basic experiments, and clinical research

to assess how the tumor microenvironment (TME) responds to immunotherapy. We’ve

developed novel computational methods for single cell spatial omics, such as

Cottrazm, to tackle challenges in spatial tumor analysis. This allows us to explore how

the TME drives the dynamic spatiotemporal evolution of tumor progression and

Youqiong Ye, PhD

Principal Investigator

Shanghai Institute of Immunology

Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

Dr. Ye is a principal

investigator at the

Shanghai Institute of

Immunology. Her research

focuses on how the spatial

tumor microenvironment

influences immune escape

mechanisms in response to

immunotherapy. A primary

goal of Dr. Ye’s team is to

identify novel therapeutic

strategies targeting

the tumor boundary

microenvironment.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 18

influences therapeutic efficacy, with particular

attention to the role of tumor boundary components in

immune escape and immunotherapy effectiveness. This

comprehensive approach enables us to better

understand the interplay between the TME and

therapeutic outcomes.

Why did you pursue spatial transcriptomics for

your research?

Although single cell transcriptomics has revolutionized

biological and medical research, a major limitation of

scRNA-seq is its inability to capture spatial information.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies have

addressed this gap by enabling gene expression

quantification in intact tissues while preserving the

spatial localization of transcripts and the threedimensional

organization of molecular processes.

In our studies, we primarily focus on the spatial

distribution of cells, cellular interactions, and network

regulation within the tumor microenvironment and its

response to immunotherapy. Therefore, the spatial

positioning of transcripts is crucial, making ST an

indispensable part of our research.

How has spatial impacted your research?

We first used ST in our research in 2021 after we

discovered that SPP1+ macrophages and FAP+ fibroblasts

were significantly enriched in colorectal cancer (CRC)

tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. At that

time, the reviewers for our publication asked us to

provide spatial evidence of the localization of these cell

types, prompting us to use the 10x Visium platform. We

found that both SPP1+ macrophages and FAP+ fibroblasts

were located at the tumor boundary, where they formed

an immune-excluded desmoplastic barrier—a dense

barrier made of fibrous connective tissue—restricting

T-cell infiltration and thus contributing to immune

evasion in colorectal cancer.

Since many of our studies use ST data, we have even

developed the computational tool Cottrazm for spatial

tumor analysis. The tool integrates ST data,

morphological information from hematoxylin and eosin

histological images, and single cell transcriptomics.

These data are then used to delineate tumor boundaries

and cell “spots” in tumor tissue, then leveraged to reveal

cell type–specific gene expression signatures.

More recently, we’ve also used tumor ST data to analyze

pan-cancer microenvironment features. This project

has focused on localizing functional enrichment of

differentially expressed genes to specific tumor

structures, teasing apart the TME’s cellular

composition, identifying cell type–specific gene

expression signatures, and characterizing cell–cell

interactions. From this, we have developed a userfriendly

database called SpatialTME that allows users to

search for, visualize, and download results.

Many of our ongoing studies continue to rely on ST,

which has provided crucial information and accelerated

our research progress.

Mapping a new path forward for

immunotherapeutic targeting of

colorectal cancers

What makes some tumors responsive to

immunotherapy but others not? Qi et al. were able

to correlate shorter progression-free survival in

CRC with the presence of two distinct cell types—

FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages—inferring

these cell types could be working synergistically.

Visium sequencing-based analysis revealed that

these two cell types were colocalized in the TME,

and these areas were enriched for pathways

associated with extracellular matrix and collagen

fibril organization. This spatial insight was crucial

to revealing how FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+

macrophages may work together to promote an

immune-restrictive TME, earmarking them as

attractive targets for future therapeutic strategies

that can improve immunotherapy responsiveness.

Explore the findings that made this one of

Nature Communications’ top 25 health science

articles of 2022 >

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 19

What considerations did you take into account when

choosing the type of spatial analysis you would use?

The choice of which spatial technology to use should

always be based on our specific biological needs so that

we select the most suitable ST method to address our

research questions.

For example, when we want to investigate how the TME

regulates treatment effects before and after therapy but

lack prior knowledge about which cells or genes are key

regulatory elements, we choose Visium HD, which can

capture the entire transcriptome. This contrasts with

using Xenium, which uses predefined gene panels.

However, as imaging-based ST technologies like Xenium

continue to expand their gene panel capabilities while

offering much larger detection areas than Visium HD,

they are becoming more attractive for specific

applications. For instance, imaging-based ST platforms

like Xenium are a great choice when working with

clinical research samples, such as tissue microarrays,

where we aim to analyze dozens of samples within a

single detection area simultaneously. They not only

reduce batch effects but also lower costs, making them

ideal for large-scale studies.

Do you have any advice or learnings to share with

people interested in getting started with spatial?

For a researcher who is new to spatial omics, the most

important step, as I mentioned in my previous response,

is to clearly define your scientific question.

Understanding the characteristics of each technical

“For instance, imaging-based

ST platforms like Xenium are a

great choice when working with

clinical research samples, such

as tissue microarrays, where we

aim to analyze dozens of samples

within a single detection area

simultaneously. They not only

reduce batch effects but also

lower costs, making them ideal

for large-scale studies.”

Visium HD spatial profiling identifies the cellular composition in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer samples treated with total neoadjuvant therapy in combination with bevacizuma.

Image credit: Ye lab.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 20

platform is crucial, as the appropriate choices should be

based on which one helps you achieve your specific

research goals. Additionally, it is essential to adjust the

experimental design based on the type of data that the

available platforms can provide.

It is also essential to familiarize yourself with the

unique features of your omics technologies. For

instance, if an experiment requires spatial

transcriptomics and spatial metabolomics or spatial

proteomics from neighboring tissue layers, the approach

(e.g., what sample type to use) may need to be adjusted

accordingly. For a study involving spatial

transcriptomics and spatial metabolomics, it is crucial

to use freshly embedded samples. In this case, using

fresh samples with the Visium HD [WT Panel] assay

would be the optimal choice. However, if the study

involves ST and antibody-based spatial proteomics,

using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples with

the Visium HD [WT Panel] assay would be a better

option. Platform flexibility allows researchers to tailor

their approach to the specific requirements of their

research, ensuring the best possible outcomes.

Are there any new directions or capabilities

you are particularly excited to see emerge in

spatial biology?

I would be particularly excited if future technologies

enable the integration of spatial multiomics—including

spatial epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and

immunomics—on the same slide or neighboring slides. I

think the successful commercialization of such

multiomic technologies would make them accessible to

more laboratories, greatly expanding their use

in research.

Additionally, I look forward to the broader application of

3D spatial omics, as this would provide even more

comprehensive insights into the complex interactions

within tissues and their spatial organization and

advance our understanding of biology at

unprecedented resolutions.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 21

Shaping future therapeutic

possibilities:

Dr. Freytag on the power of spatial

insights in clinical research

What is your lab’s research focus?

I co-lead a lab with a unique arrangement. There are three of us in the lab: I’m a

computational biologist, Dr. Sarah Best is a cancer biologist by training, and Dr. Jim

Whittle is a neuro-oncologist. That probably hints at what we do, which is thinking

very deeply about brain cancer. In particular, we focus on the development of new

Saskia Freytag, PhD

Laboratory Head, Brain Cancer Research Lab

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of

Medical Research

Dr. Freytag is the head of

the Brain Cancer Research

Lab at The Walter and Eliza

Hall Institute of Medical

Research. Alongside

research oncologist Dr.

Sarah Best and clinician Dr.

Jim Whittle, she investigates

molecular features of

brain cancer that can

inform the development of

future therapies.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 22

personalized therapies that can fundamentally shift

outcomes for individuals with brain cancer.

We do this by harnessing Sarah’s and my expertise

investigating molecular and cellular features. When we

say molecular, we’re extremely interested in the

metabolism that defines these tumors, with the goal of

translating what we find there into meaningful

clinical advances.

The work we do is firmly grounded in a patient-centered

approach. In practice, this means that we have many

programs that go from bench to bedside. We’re trying to

develop more accurate diagnostics and also discover

new therapeutic strategies for these really aggressive

tumors. We then try to push that into our globally

unique clinical trials platform that is led by

Dr. Whittle and established with help from the

Victorian Government.

We have pioneered an approach where we’re sampling

pre- and post-treatment biopsies. Subjects in these trials

undergo a biopsy, receive treatment for a certain

duration, and then come back and get a full tumor

resection. These precious biopsy samples that we’re

collecting for research—these matched samples—really

allow us to investigate, with an unprecedented detail,

how therapies work on a molecular level. We can also get

insights into how they don’t work.

That then feeds back into our basic science pipeline

where we’re designing and developing new therapies.

So it is this iterative loop that we’re trying to do, which

hopefully means that we’re finding ways to make care

for brain cancer patients much more effective in

the future.

What types of insights into therapeutic mechanisms

have you observed?

We’ve only been up and running for around three and a

half years as a lab. We haven’t had any compounds or

therapies that we’ve developed actually go into clinical

trials. However, we have done clinical trials. So we’ve

been able to work in parts of the [drug development]

pipeline, but have not yet taken a compound all the way.

Immunofluorescence staining post-acquisition of Xenium spatial transcriptomics, revealing cell morphology (green = GFAP protein expression). Sample represents a resected tumor

from an individual with a low-grade glioma.

Image credit: Brain Cancer Research Lab, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 23

Recently, we’ve been fortunate to finish the first clinical

trial that went through this perioperative platform

design. It was for an IDH [isocitrate dehydrogenase]

mutant inhibitor. Mutations in the IDH enzyme have

been linked to many gliomas and alter DNA

hydroxymethylation, gene expression patterns, cell

differentiation, and the tumor microenvironment. It

was really fascinating to use these matched tumor

samples to learn how this inhibitor used to treat

gliomas works.

I think our research could really help shed some light on

this. We also believe it will help us understand the

mechanisms of some off-target effects that we’ve

observed, which seem to be beneficial for some

individuals in terms of relieving seizures that are

associated with gliomas.

Why did you pursue spatial transcriptomics for

your research?

When we started, we were really aware that

metabolomics and metabolite activity in brain cancers

is something that has been understudied and could

potentially be utilized in [the future] to treat patients.

So we’re really interested in establishing that platform

in combination with spatial transcriptomics because I

think that those things need to go hand in hand.

Additionally, while there are great spatial proteomics

platforms out there, they are limited in terms of the

markers that you can look at. Because we were

interested in the composition of our samples and with

brain cancer being extremely heterogeneous, with cell

populations that are pretty similar to each other, it was

obvious to us that a proteomics-limited panel wouldn’t

let us see that diversity. Having access to a spatial

transcriptomics method, like Xenium panels that look at

500 genes, allows us to be able to delineate all these

populations properly.

These spatial technologies are essential for our

understanding of brain cancer because these tumors are

so highly heterogeneous and they infiltrate into the

normal brain, which is a tissue that is already

poorly understood.

The traditional bulk or single cell approaches obviously

lose critical spatial context that is an essential

component in shaping tumor behavior and this

treatment response that we’re investigating in our

clinical trials. By preserving this, what we have been

finding in our clinical research samples, using the

Xenium platform, is that we can now begin to

understand how tumor cells interact with the

microenvironment and how they respond differently to

therapy depending on what microenvironment they

are in.

Additionally, I think what’s really powerful about this

platform is that we can actually overcome some of the

drawbacks in these types of clinical trials, where sample

variability is something that we’re always concerned

with. Whether we sample at the tumor edge or more in

the center of the tumor is something we can’t control in

a very complex clinical trial design, where subjects

undergo a very aggressive sort of surgery. We don’t

always know what the surgeon will be able to get. But

the spatial context of what tissue samples we do get,

actually allows us to interpret similar regions, pre- and

post-treatment, and see what has changed in them

without being confounded by the cellular composition.

Dissecting how gliomas respond to IDH inhibition

Although IDH mutations are known to be a key

driver of many low-grade gliomas, treatment with

targeted IDH inhibitors is relatively new. Using

tumor biopsies from the first ever single-arm

perioperative trial (NCT05577416) for IDH inhibition,

Drummond et al. leveraged Xenium imaging-based

analysis to map the TME of matched pre- and

post-treatment tumors. This spatial analysis was

critical in understanding how treatment changes

the TME to alter synaptic signaling, suggesting a

potential mechanism by which IDH inhibition

reduces seizures.

Check out this trailblazing clinical research in

Nature Medicine >

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 24

In one of your recent papers, you compared

several commercially available spatial options and

concluded that the Xenium platform was more

compatible, more useful. Can you share a bit more

about that?

We did a lot of comparisons when we first started trying

to narrow down the spatial platform we wanted to use.

We knew we wanted to be a lab that uses this really

heavily, and key considerations for us were what sort of

resolution we could get, the gene panel flexibility, the

reproducibility of the platform across samples, and, of

course, the compatibility with our clinical

trial workflow.

In the end, we were simply most impressed with the

reliability and the data quality we got from Xenium.

We’ve now processed over 50 samples in the lab and

have had minimal technical failures. I think we’ve had

one in all of this time, and that’s probably because the

sample quality wasn’t great, so nothing to do with the

instrument. The instrument is super reliable. That’s

really important when you’re doing a clinical trial and

the research sample that you have is really precious. We

don’t want to put these samples on an instrument that

isn’t reliable and doesn’t give us great data that we want

to analyze in the end. These individuals participating in

the clinical trial have agreed to undergo two brain

surgeries to allow for tissue samples for this research to

be collected. We want to be sure that those samples go to

maximal effect.

Do you have any advice or any top learnings for

people that are interested in getting started with

spatial transcriptomics?

It can be pretty overwhelming to start, and what I would

have liked to know is that you make use of every slide in

a maximal way by putting multiple tissues on it. I think

we’ve now stretched this to using even the tiniest speck

of empty space by putting some of our neurosphere or

organoid models on there. When you have free space, it’s

wasted space, so you might as well utilize the entire

imageable area.

In terms of what genes to look at, I really love custom

panels. I’m a big fan of them because they keep costs

down while focusing on the biology that you’re

interested in. However, it can be overwhelming to start

designing one. But I think once you get your feet wet,

you’ll be amazed by how much you find.

Finally, I have been a big proponent that cell

segmentation isn’t as important as people may believe.

Especially if your primary interest is in the tissue

composition and cell identities. In this case, I think you

can get away with just using the nuclei or the broader

watershed segmentation that 10x Genomics pioneered

at the start. I say this because cell segmentation is hard,

and you’re going to spend a lot of time doing this when

simplicity might get you exactly the same information.

In fact, we’ve got a publication on bioRxiv at the

moment, where we compared different types of cell

segmentation. We looked at nuclei segmentation and an

actual cell segmentation using a post-staining approach

that we did in the lab. This was prior to Xenium making

multimodal cell segmentation available.

What we found was that the nuclei segmentation and

the other approaches were essentially very similar when

calling the composition of the sample. The manual cell

segmentation staining approach we had developed,

however, was taking us hundreds of hours to compute

and also quite a significant amount of labor to get done.

So, the question is then: is it worth it? There are

applications where that absolutely is necessary, but I

think people need to really carefully think about if their

application is one where it’s truly needed.

“The instrument is super reliable.

That’s really important when

you’re doing a clinical trial and

the research sample that you

have is really precious.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 25

What kind of new directions or capabilities

are you particularly excited to see emerge in

spatial biology?

I’m really fascinated with the epigenetic features that

we can now look at spatially. I would love for there to be

a good platform that allowed spatial analysis of DNA

methylation and did it cheaply. I don’t think we’re quite

there yet, but, for brain cancer, the epigenome is crucial

in defining these tumors. It also probably plays a big

role in their plasticity and how they respond to

treatment. We also think these processes are driven by

the niches these cells live in. Being able to observe that

would be really cool. There are so many open questions

in brain cancer surrounding the epigenetic markers that

have been found to show prognostic value and whether

there are areas in the brain tumor where they are really

abundant or absent.

What do you think your future research direction

will be?

We have several trials starting this year focused on

super aggressive brain cancer, which almost always kills

you within one year. In those studies, we’ll be using

immunotherapies that are, for the first time, available to

patients in Australia. It’ll be really interesting to

investigate how the immune system reacts in the tumor

itself following these treatments, which is something we

haven’t been able to research before.

“It can be pretty overwhelming to

start, and what I would have liked

to know is that you make use of

every slide in a maximal way by

putting multiple tissues on it.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 26

Spencer Watson, PhD

Senior Research Fellow, Biomedical Data

Science Center

University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Dr. Watson is a Senior

Research Fellow at the

University of Lausanne’s

Biomedical Data Science

Center. As a postdoctoral

researcher in the laboratory

of Dr. Johanna Joyce, he

investigated the cellular

mechanisms responsible

for glioblastoma recurrence

in the hopes of finding

better treatments.

Unveiling tumor secrets:

Dr. Watson’s spatial multiomics

approach to glioblastoma research

What made you decide to use spatial transcriptomics for your research?

For me, it was primarily a question-driven choice. I had very specific questions about

the post-treatment tumor microenvironment niche and I wasn’t getting answers from

disaggregated single cell omics analyses. It was critical that we saw what was

happening and where it was happening.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 27

How would you say spatial has impacted

your research?

It was very transformative for my project. Especially

going from looking at disaggregated data and having all

these questions about, “Is this actually happening in

regions of fibrosis? Is it happening anywhere near the

tumor cells?”

Being able to look at an image, combine protein

expression and gene expression, and everything all in

one to say, “Yes, we know what is happening, and we

know exactly where it’s happening.” That has allowed us

to uncover some unique biology in our latest analysis of

the brain tumor microenvironment.

Tell us a little bit more about your latest

research findings.

Our recent Cancer Cell article, “Fibrotic response to

anti-CSF-1R therapy potentiates glioblastoma

recurrence,” follows up on previous findings where we

were using anti-CSF-1R inhibitors to re-educate

macrophages in glioblastoma from a pro-tumor

phenotype back into an anti-tumor phenotype. It was

really successful in massively shrinking these huge

tumors in the mouse model. However, we kept seeing

rebound tumor recurrence.

The super interesting thing we found is that, every time

there was a recurrence, it was always associated with a

fibrotic glial scar. In cancer research, you don’t get a lot

of 100% phenomena, so whenever you see that you

definitely need to follow up.

Our idea was that maybe these fibrotic scars are

causing—or at least potentiating—recurrence, but this

is a very complicated environment. It’s very dense.

There are a lot of cellular players involved. We needed a

lot of different omic modalities. We had single cell RNAseq,

spatial proteomics, mass spectrometry proteomics,

and spatial transcriptomics.

The particularly useful thing for us was integrating all

these together to create a multimodal spatial dataset

that allowed us to identify that the cellular mitigator of

this fibrotic niche was encapsulating tumor cells.

Essentially, it was protecting them and driving them to

a state of dormancy where they’re safe from other

treatments and was protecting them from immune

surveillance. With the spatial omic dataset, we were able

to identify what the precise cell type was that was

causing this and what signals were activating it. That

allows us to build a drug treatment strategy to block the

cellular response.

And our hypothesis was correct. Eliminating fibrosis

massively improved the efficacy of the immunotherapy.

That’s something that we are very much looking forward

to moving forward with in other clinical directions. The

future of this project and what we’re doing now is

translating this into the patient setting. We found

evidence for it in the patient setting in the paper, and

now we want to go all-in on patient samples and

massively increase the scale because what we’ve seen

already is there’s so much heterogeneity there. By going

high throughput and high content with that same

spatial multiomic depth, we [hope to] be able to identify

other combination treatments that can counter the

negative side effects of many of the treatments we use in

the clinic.

What considerations did you take into account

when choosing which type of spatial technology you

would like to use?

The most significant consideration, for me, is that it had

to be single cell and, ideally, it had to be nondestructive

and image-based so that it could combine with some of

our other modalities.

“I had very specific questions

about the post-treatment tumor

microenvironment niche and

I wasn’t getting answers from

disaggregated single cell omics

analyses. It was critical that we

saw what was happening and

where it was happening.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 28

Second was how robust the data was. We saw a lot of

other approaches that could analyze more genes, but

then there were too many questions about the quality of

the data you were getting. I think having something that

gives fewer genes, but gives you absolute faith and

confidence in the data you are getting, is essential.

What advice or top learnings would you share with

people interested in getting started with spatial? Is

there anything you would have liked to know before

you started spatial yourself?

First, I want to emphasize how important it is to have

single cell data to complement the spatial

transcriptomic data. Having that combination and

synergy gave us the ability to achieve more

transcriptional depth and project spatial signatures

onto the disaggregated data. That opened up a lot of

doors for us.

Next, I would say to never do it as part of a revision,

mainly because of the amount of interesting questions

that you can answer once you have it. Spatial is

something to do at the start of a project rather than at

the end; otherwise, you’ll add several years to your

analysis chasing down all the interesting leads.

Also, make sure that you actually have a question that is

applicable to spatial. I think a lot of people feel that they

have to do it for grant purposes or something similar.

But, if they don’t have a defined question that spatial

resolution will answer, they can spend a lot of

unnecessary analysis time trying to make use of

the data.

Are there any new directions or capabilities you’re

particularly excited to see emerge in spatial

biology?

There is a lot of focus on spatial proteomics. It was the

method of the year; previously, it was spatial

transcriptomics. But I feel like it’s all going to be about

multiomics, about how many data types can you

integrate, so that we can ask these computational

systems biology–level questions of emergent features

that you would never get from even one of these

powerful approaches.

I think increasingly you’re going to see protein with

transcriptomics and metabolomics. Spatial ATAC-seq

will probably come along as well. The idea of just doing

one of these may seem like an anachronism in

five years.

Reimaging our understanding of glioblastoma dynamics

More than 90% of patients with glioblastoma, the most common and aggressive

brain cancer, have their tumors recur even after treatment. Watson et al. integrated

Xenium single cell spatial imaging insights with proteomics and traditional single

cell RNA-sequencing to define the association between fibrotic scars and

glioblastoma recurrence. Critically, these high-resolution multiomic insights

enabled the identification of a multidrug treatment regime to limit scar formation

and, therefore, boost treatment efficacy, which showed promising preclinical results.

See the stunning data that earned a cover spot in Cancer Cell >

“Being able to look at an image,

combine protein expression and

gene expression, and everything

all in one to say, “Yes, we know

what is happening, and we know

exactly where it’s happening.”

That has allowed us to uncover

some unique biology in our

latest analysis of the brain tumor

microenvironment.”

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 29

What do you feel is the biggest benefit of doing all

these modalities simultaneously?

Especially in the cancer field, we are working with very

precious samples, and we really need to get the most out

of them. This sample was a major contribution from a

patient. We should make sure that we are asking every

possible question and getting every possible thing that

we can get out of it, not just for us but also so the people

who come after us can continue to use this data.

By making these massively deep datasets and making

them publicly available, it has this snowball effect

where we asked our question of it, but there are many

other researchers who can now ask their questions of

the same data.

Is there anything else you would like to highlight?

I think the most exciting thing now is scale. Cancer is so

heterogeneous that doing 3 or 4, even 10 or 20, samples

barely scratches the surface of the variability. When we

scale this up to hundreds and beyond, that’s when the

AI revolution becomes really exciting, because then we

can train AI models that saturate all the noise in cancer

and overcome this burden of heterogeneity. What these

AI models can find that we’ve never appreciated, that’s

going to be the really exciting stuff in the next 5 to

10 years.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 30

Make your spatial goals a reality

As the incredible researchers featured in this eBook have shown, spatial transcriptomics enables powerful

insights and opens up new areas of investigations.

If you are ready to journey into the world of spatial transcriptomics and gain new levels of understanding in

your research, we’re here to help turn your spatial goals into real breakthroughs.

The 10x Genomics Xenium Spatial and Visium Spatial platforms have been designed to let researchers like

you explore tissue landscapes with exceptional precision, flexibility, and reliability. Get to know a little more

about each platform below, then follow the QR codes to continue your journey.

Visium platform

A whole transcriptome spatial gene expression platform,

Visum expands single cell–scale spatial discovery with

the broadest view of gene expression.

Why choose Visium?

Whole transcriptome analysis with single

cell–scale resolution

Broad discovery power with a 3’ poly(A)-based assay

& NGS read-out

Working with archival or pre-sectioned slides

Xenium platform

A best-in-class ultra-high plex in situ technology,

Xenium delivers robust single cell spatial discovery

with unmatched customization.

Why choose Xenium?

Subcellular resolution & higher per gene sensitivity

Custom panels for targets & species

of interest

Large imageable area provides flexibility to run

multiple tissue sections per slide

Scan the QR code

to learn more about

the Xenium platform.

Scan the QR code

to learn more about

the Visium platform.

10x Genomics Perspectives from Global Pioneers in Spatial 31

Selected publications and resources

Dr. Miguel Reina-Campos

Reina-Campos M, et al. Metabolic programs of T cell

tissue residency empower tumour immunity. Nature

621: 179–187 (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06483-w

Reina-Campos M, et al. ImmGenMaps, an open-source

cartography of the immune system. Nat Immunol 26:

637–638 (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41590-025-02119-5

To access ImmGenMaps datasets, visit

https://www.immgen.org/ImmGenMaps/

Dr. Amanda Poholek

Spatial cytokine microniches direct T helper cell

pathways that drive allergic asthma. Nat Immunol 25:

1999–2000 (2024). doi: 10.1038/s41590-024-01987-7

Dr. Nicholas Banovich

Amancherla K, et al. Dynamic responses to rejection in

the transplanted human heart revealed through spatial

transcriptomics. bioRxiv (2025).

Mallapragada S, et al. A spatial transcriptomic atlas of

acute neonatal lung injury across development and

disease severity. bioRxiv (2025).

Dr. Youqiong Ye

Du Y, et al. Integration of pan-cancer single-cell and