X-Ray Spectroscopy

Explore X-ray spectroscopy’s wide reach in research and its ongoing impact on chemistry and life sciences.

X-rays, a type of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths from 0.01 to 10 nanometers, pack enough energy to pierce materials and interact with inner-shell electrons.1 When they hit a sample, X-rays can be absorbed, scattered or re-emitted as unique radiation, creating “fingerprints” that reveal an atom’s identity. These signatures power a wide range of scientific breakthroughs.

Since Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery in the late 19th century and Henry Moseley’s finding that emission lines are tied to atomic numbers,2 X-ray spectroscopy has grown into a vital toolset. It peers into atoms’ inner shells, uncovering elemental makeup and structures invisible to visible light. In analytical chemistry, it spots trace elements and measures concentrations in tricky mixes. For life sciences, it maps biomolecule structures, guides drug design and tracks metals in tissues – key for health insights.3

This versatility stems from its diverse branches. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) reveals surface chemistry, while energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), paired with microscopy, maps elements. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) offers quick, non-destructive checks and X-ray absorption (XAS) and emission (XES) explore local environments. X-ray diffraction (XRD) decodes crystalline layouts, rounding out the family.

This article kicks off with X-ray basics and spectrum reading, then dives into XPS, EDX, XRF, XAS, XES and XRD – explaining how they work, what they reveal and where they shine. By the end, you will grasp X-ray spectroscopy’s wide reach and its ongoing impact on chemistry and life sciences.

Understanding an X-ray spectrum

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX or EDS)

- EDS analysis/EDX analysis

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF)

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)

X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES)

X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD)

SEM-EDX – Combining X-ray spectroscopy with other techniques

What is X-ray spectroscopy?

X-ray spectroscopy is a set of techniques that use X-rays to uncover a material’s elemental makeup, electronic structure and atomic layout. At its heart, it taps into X-rays’ ability – electromagnetic waves with 0.01 to 10 nanometer wavelengths – to penetrate matter and jostle inner-shell electrons.4 This triggers emissions, absorptions or scatters that act as unique “signatures,” revealing an element’s identity and its chemical surroundings.

The field took off in the early 20th century after Wilhelm Röntgen’s 1895 X-ray discovery. Henry Moseley’s 1913 work linked X-ray line frequencies to atomic numbers, shaping the periodic table, while the Braggs’ X-ray diffraction breakthrough mapped crystal atoms. From vacuum tubes to synchrotrons, instrumentation leaps have boosted its precision and scope over time.4

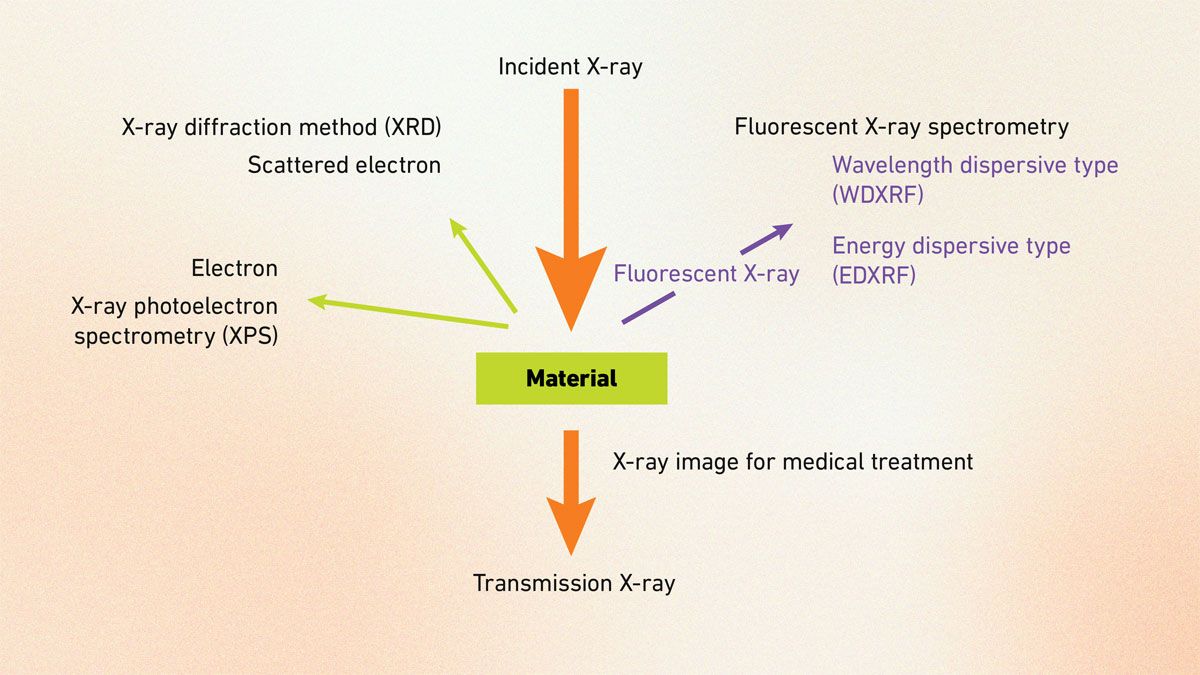

Today, it branches into diverse methods based on X-ray interactions (Figure 1):

- XAS tracks energy-dependent absorption to reveal local bonding.

- XRF detects secondary emissions for non-destructive elemental checks.

- XPS measures photoelectron energy for surface insights.

- EDX, often with scanning electron microscopy (SEM), maps elements via electron beams.

- XES probes occupied electronic states.

- XRD decodes crystal structures through interference.

Together, these techniques leverage X-rays’ inner-shell probing power, offering complementary views – from surface details to bulk structures – making X-ray spectroscopy vital for chemistry, life sciences and materials research.

Figure 1: Diagram of X-ray spectroscopy techniques, grouped by interaction type. Credit: Technology Networks.

Understanding an X-ray spectrum

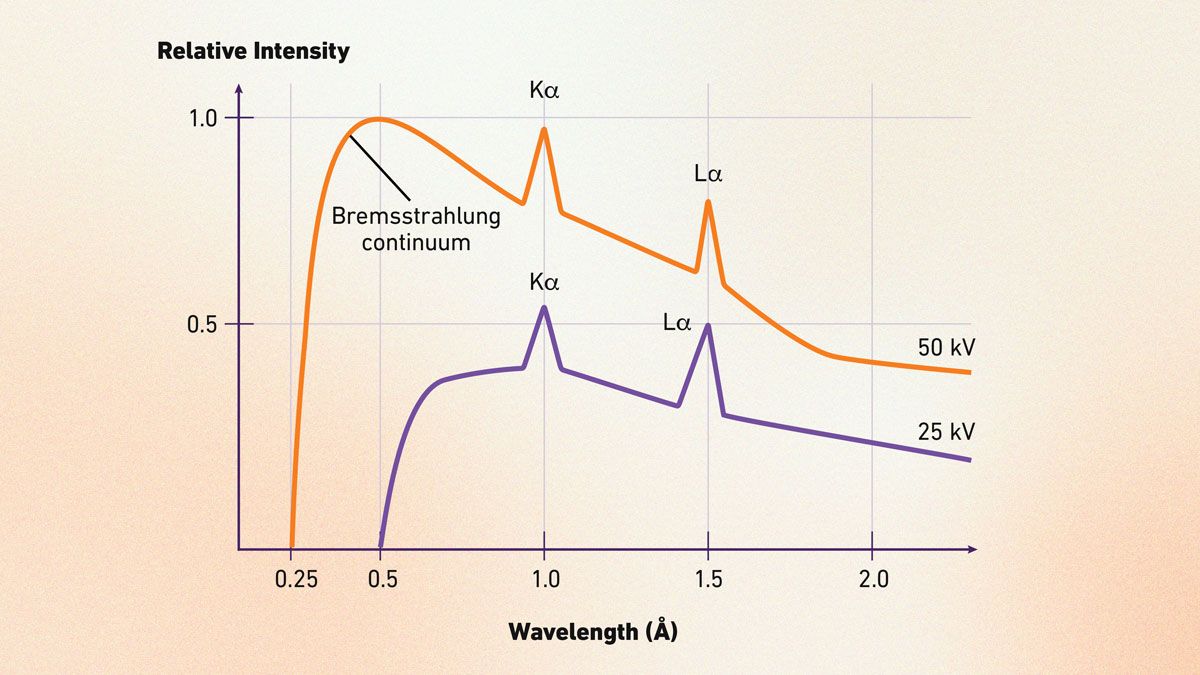

An X-ray spectrum charts photon intensity against energy (in keV) or wavelength (in Å), blending a smooth background with sharp peaks that act like an element’s signature (Figure 2).5 The background, or Bremsstrahlung radiation, comes from electrons slowing down when hitting a target, though synchrotrons may show scattered X-rays instead. The peaks, like Kα lines, stem from inner-shell electron jumps.

The horizontal axis shows photon energy or wavelength, while the vertical axis tracks intensity (counts per second). The background’s end –the Duane–Hunt limit – ties to the X-ray tube’s voltage.5 These element-specific peaks power techniques like XRF for quick identification.

Henry Moseley’s 1913 discovery showed peak energies scale with atomic number (Z), with the square root of frequency rising linearly, cementing Z as the periodic table’s backbone.6

Beyond spotting elements, spectra reveal a material’s electronic makeup. Emission lines hint at occupied states (e.g., valence bands), while absorption probes unoccupied ones (e.g., band gaps, Fermi levels). Inner-shell vacancies can muddy the picture, overlapping with band structures, but this duality makes X-ray spectroscopy a go-to for both elemental and electronic insights.

Figure 2: Annotated example of an X-ray spectrum showing Bremsstrahlung continuum and characteristic Kα and Lα peaks. Credit: Technology Networks.

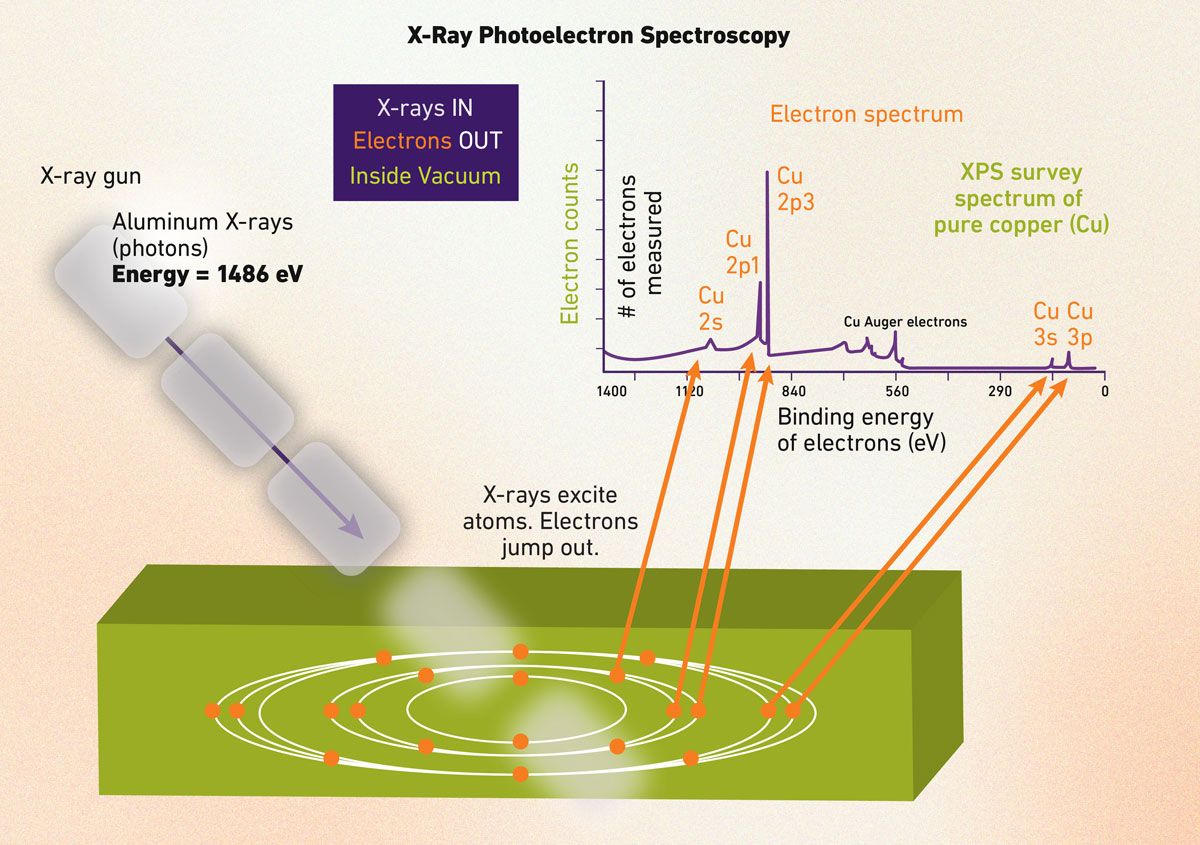

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS is a top tool for exploring surface chemistry in solids. It hinges on the photoelectric effect, where X-rays knock out electrons from a material’s core or valence levels when their energy exceeds the electron’s binding energy – first explained by Einstein. This ejects electrons and measuring their kinetic energy (KE) via 𝐸𝐵 = ℎ𝜈 – 𝐾𝐸 − 𝜙 (where ℎ𝜈 is photon energy and 𝜙 is the work function) reveals binding energy (𝐸𝐵), unlocking surface details (Figure 3).

XPS is surface-focused because only electrons from the top 1–10 nm escape unscathed by inelastic scattering.7 Its spectrum plots intensity versus binding energy (eV), showing sharp peaks (e.g., C 1s, O 1s) that identify all elements except hydrogen and helium. Chemical shifts in peak positions hint at oxidation states or bonding – like higher shifts in transition metals signaling greater oxidation.7

This makes XPS ideal for diverse applications: it analyzes protein coatings on implants in biomaterials or tracks oxidation in catalysts. Newer ambient-pressure XPS (AP-XPS) studies surfaces in real-time under gas or liquid conditions, boosting energy research.8 In short, XPS blends elemental and chemical insights at the nanoscale.

Figure 3: Schematic of XPS: an X-ray photon triggers the photoelectric effect, ejecting a core electron; the analyzer measures its kinetic energy to calculate binding energy, revealing surface chemistry alongside an example XPS spectrum with labeled peaks showing chemical shifts for interpreting bonding states. Credit: Technology Networks.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX or EDS)

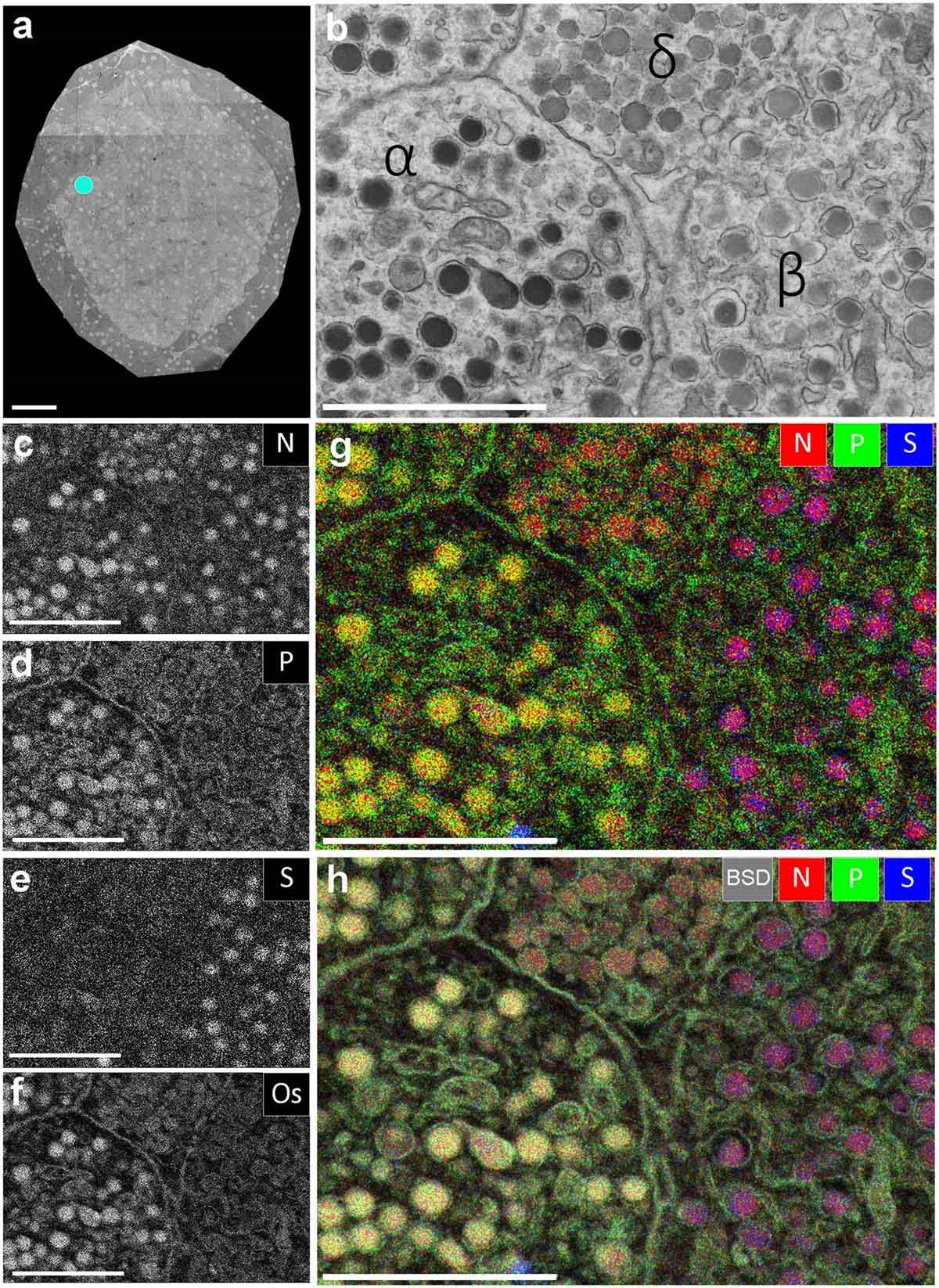

EDX or EDS is a handy technique that spots and maps elements in samples at micro- and nanoscale levels. Paired with SEM or transmission electron microscopy (TEM), it uses an electron beam to excite atoms, releasing characteristic X-rays that reveal element types and locations.1 This link between structure and chemistry shines in life sciences, decoding elemental roles in cells or tissues.

The process begins with the beam knocking out inner-shell electrons, creating vacancies filled by outer electrons that emit unique X-rays (e.g., Kα, Kβ lines). A silicon drift detector (SDD) catches these X-rays, producing a spectrum of intensity versus energy.2 EDX stands out with mapping: scanning the beam generates color-coded maps where bright spots show element concentrations – key for tracking metals in biomolecules or spotting nanomaterials’ impurities (see Figure 4).

It’s widely used in analytical chemistry to quantify elements (boron to uranium) for alloys or impurities, and in life sciences to map calcium in bones, trace metals in cells or nanoparticles in drugs – offering clues to health or disease.9 Its speed and non-destructive nature suit forensics, environmental and pharmaceutical studies too.

EDS analysis/EDX analysis

EDX analysis follows a simple flow:

- Excitation: The electron beam triggers X-rays in a small sample volume (nanometers to micrometers).

- Detection: An SDD measures X-ray energies (1–20 keV), turning them into signals.

- Spectrum generation: Software plots elemental peaks, subtracting Bremsstrahlung background.

- Interpretation and mapping: Peaks match databases (e.g., NIST) for identification; maps use colors to show distributions, like iron in tissues.10 An example elemental map is shown in Figure 4.

EDX offers quick, in situ results with minimal preparation, pairing well with SEM. Yet, it misses light elements (e.g., hydrogen), faces peak overlaps and risks beam damage—mitigated by low-voltage modes for biology.10 Though resolution (~100–150 eV) lags behind alternatives, SDD advances enable real-time mapping for everyday use.

Figure 4: EDX defines cell-types and subcellular structures and organelles in EM images. Credit: Image by Marijke Scotuzzi et al. reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF)

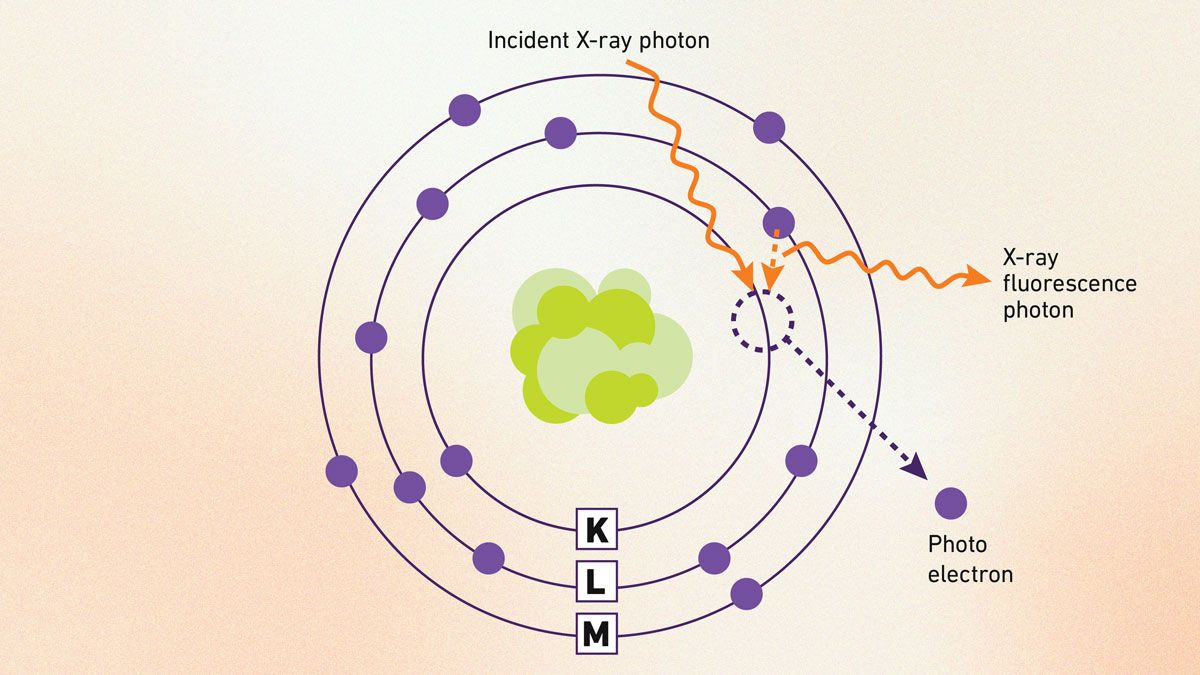

XRF is a non-destructive way to spot and measure elements in a sample by analyzing their unique emitted X-rays. It works by blasting the material with high-energy X-rays, ejecting inner-shell electrons and creating vacancies filled by outer electrons, which release fluorescent X-rays like an atomic identity tag (Figure 5). These X-rays are detected and turned into a spectrum where peaks show elements and their heights hint at amounts, simplifying analysis even for tough samples.

Variants include energy-dispersive XRF (EDXRF) for quick, portable checks with a detector, and wavelength-dispersive XRF (WDXRF) for sharper results using crystals.11 Advanced types like micro-XRF map tiny areas, while synchrotron XRF tracks trace metals in biology.12 Unlike EDX, XRF’s X-ray use digs deeper for bulk insights.

It’s a go-to in analytical chemistry for testing alloys or pollutants, and in life sciences for tracing metals in tissues or foods to spot health issues – all without harm. It also shines in archaeology and forensics. For more, check out X-ray fluorescence: Theory, practice, and applications.

Figure 5: Schematic of XRF process showing X-ray excitation, electron ejection and fluorescent emission. Credit: Technology Networks.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)

XAS is a powerful method that zooms in on the local structure and electronic traits of specific elements in a material, like a close-up lens on atoms. It works by tuning high-energy X-rays to an element’s absorption edge – where X-rays kick core electrons to higher levels, causing a distinct absorption spike (Figure 6).7 This unique edge pinpoints elements and their surroundings.

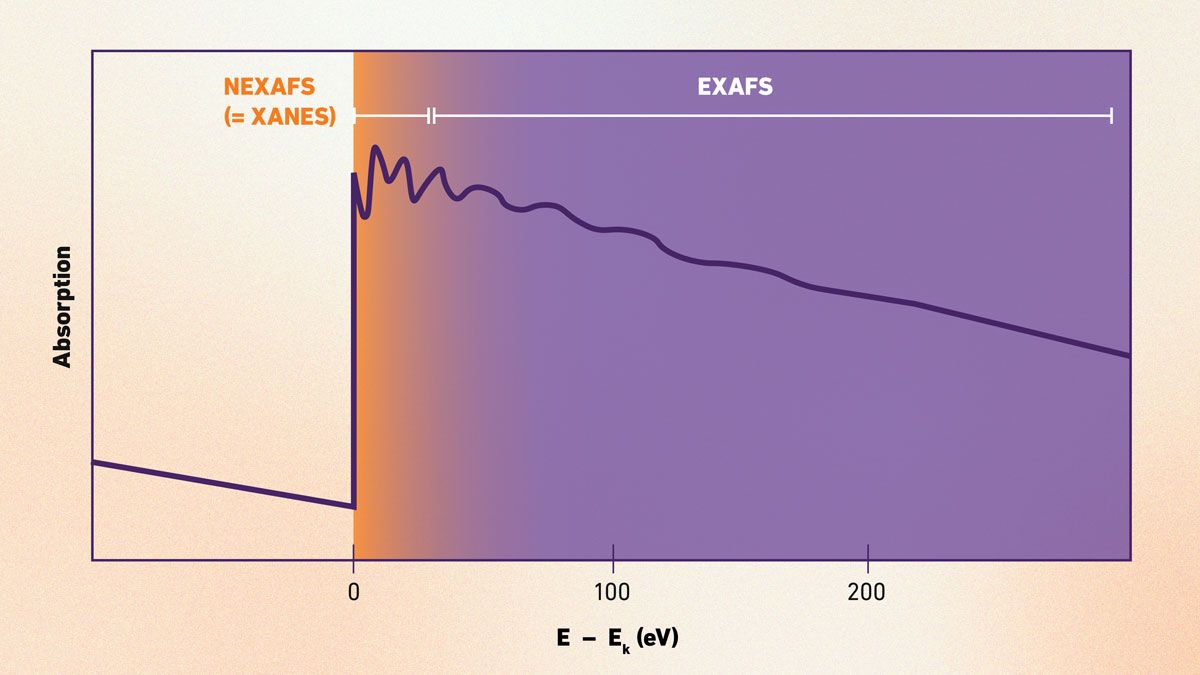

The technique splits into key methods: X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) reveals oxidation states and arrangements within 50 eV of the edge, while extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) tracks electron scattering ripples beyond 30 eV to gauge coordination and distances.13 Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) adds depth by analyzing energy losses during transitions, uncovering bonding details. Together, they decode chemical environments.

Synchrotrons boost XAS with tunable X-rays, enabling analysis of solids, liquids or traces via transmission, fluorescence or electron yield modes. Advanced forms like high-energy resolution fluorescence-detected XAS (HERFD-XAS) and RIXS sharpen focus, perfect for fragile biological samples.

XAS shines in catalysis, tracking reaction shifts, and life sciences, mapping metal cofactors (e.g., iron in enzymes) or pollutants in tissues for health insights.14 It also helps materials science decode disordered structures, complementing other X-ray tools across diverse fields.

Figure 6: Example XAS spectrum displaying the XANES region with a sharp absorption edge and the EXAFS region with oscillatory patterns. Credit: Technology Networks.

X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES)

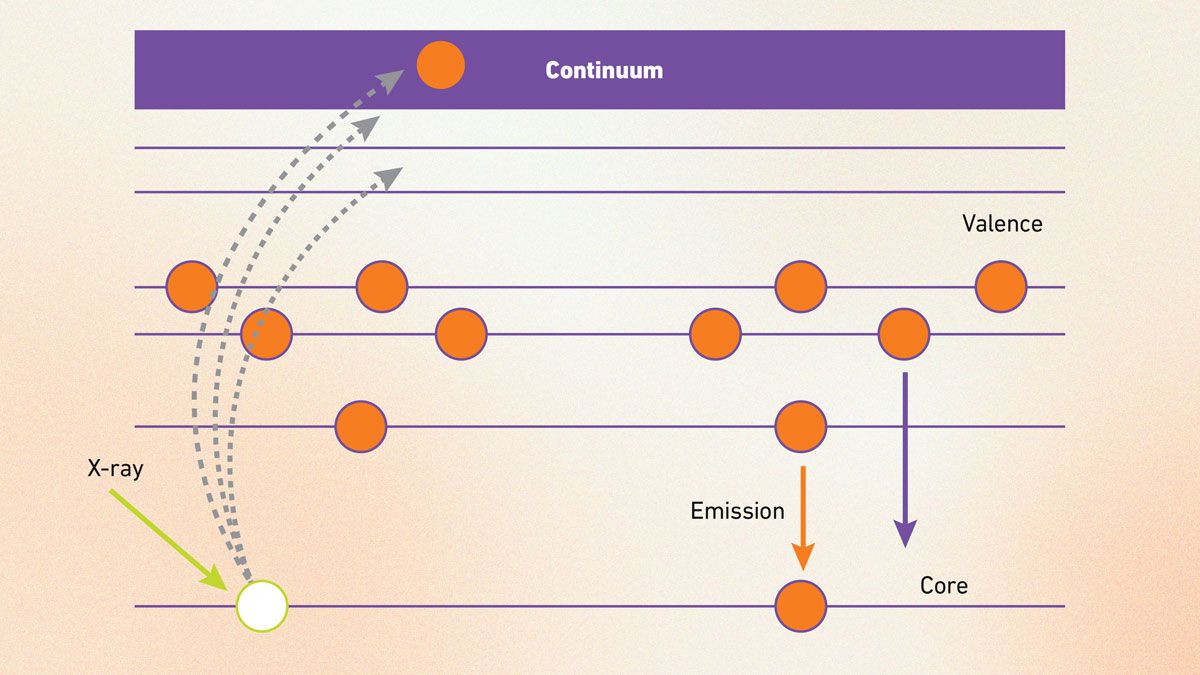

XES is a technique that homes in on the occupied electronic states of elements by detecting the X-rays they emit when excited. It works by hitting an atom with a high-energy X-ray to eject a core electron, leaving a gap filled by an outer electron that releases a secondary X-ray – its energy and intensity reveal details like spin or oxidation state (Figure 7).13 This makes XES great for probing atomic environments.

Unlike XRF, which just identifies elements, XES digs into emission details to uncover electronic setups and bonds. It aligns more with XAS, but while XAS explores unoccupied states, XES focuses on filled ones, adding a fresh perspective.

XES excels in chemistry, biology and materials science – tracking oxidation shifts in catalysis or manganese states in photosystem II for photosynthesis insights.14 High-resolution and resonant XES (RXES), boosted by synchrotrons or XFELs, enable real-time reaction monitoring, ideal for dynamic studies.

Figure 7: Illustration of secondary X-ray emission. Credit: Technology Networks.

X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD)

XRD is a proven technique that maps the atomic layout and crystalline structure of materials, like a blueprint of their inner order. It works by firing a focused X-ray beam at a crystal, where the atomic pattern scatters X-rays, creating constructive interference at specific angles – pioneered by von Laue and the Braggs. This follows Bragg’s law (nλ = 2d sin θ), where n is an integer, λ is wavelength, d is plane spacing and θ is the angle, producing a pattern that reveals the structure.

These patterns act as “fingerprints” for identifying crystals, with peak positions and intensities unveiling lattice constants, phases and defects. Advanced methods like Rietveld refinement and powder diffraction tackle complex materials like alloys or nanoparticles, enhanced by computational tools.

XRD’s non-destructive edge makes it key in structural biology for decoding proteins, materials science for analyzing ceramics and fields like geology or pharma for drug forms.3 For more, see X-ray diffraction (XRD) – XRD principle, XRD analysis and applications.

SEM-EDX – Combining X-ray spectroscopy with other techniques

X-ray spectroscopy teams up with other methods like SEM in SEM-EDX to deliver a powerful mix of imaging and elemental analysis for surface studies. In SEM-EDX, a focused electron beam scans the sample, creating detailed images of its shape and texture while also triggering X-rays from atom interactions, which an EDX detector captures to identify elements.2 This fusion provides a dual perspective – structure and composition – in one view.

The EDX spectrum plots X-ray intensity versus energy, with peaks flagging specific elements for quick identification and, with calibration, approximate amounts.2 A key perk is elemental mapping, where color overlays on SEM images reveal element locations, linking form to makeup – like spotting impurities or phases at a glance. This combination bridges visual and chemical insights.

Beyond SEM, X-ray spectroscopy pairs with techniques like TEM for nanoscale elemental mapping or XRD for structural and compositional correlation. SEM-EDX excels in materials science, unveiling alloy phases, and life sciences, probing biominerals or nanoparticles in tissues.10 It’s also crucial for forensics and environmental analysis. Unlike XRD’s broad patterns or XRF’s bulk focus, SEM-EDX zooms into micro-details, enhancing multi-scale understanding.

Comparing X-ray spectroscopy techniques

X-ray spectroscopy techniques all harness the interaction of X-rays with matter, but each zeroes in on different details, offering a rich toolkit for material analysis. Some focus on surface layers, others decode bulk crystal layouts and a few uncover electronic nuances – making them perfect partners for a full picture of a sample’s properties.

Table 1 breaks down the key methods covered – XPS, EDX, XRF, XAS, XES, XRD and SEM-EDX – comparing their physical principles, the insights they provide, analysis depth and applications. This overview highlights why these techniques are essential across diverse fields, from unraveling protein structures to solving archaeological puzzles.

Table 1. Comparison of X-ray spectroscopy techniques.

| Technique | Physical Principle | Information Obtained | Depth of Analysis | Example Applications |

| XPS | Photoelectric effect (photoelectron kinetic energy) | Surface composition, oxidation states, chemical bonding | ~1–10 nm | Catalyst surfaces, biomaterials |

| EDX/EDS | Characteristic X-ray emission from electron beam | Elemental identification, semi-quantification | ~1–2 μm (SEM/TEM volume) | Alloy phases, biominerals mapping |

| XRF | X-ray-induced fluorescence | Bulk elemental composition, trace elements | μm to mm (sample-dependent) | Archaeology, environmental monitoring |

| XAS | Energy-dependent X-ray absorption | Local structure, oxidation state, coordination | Bulk (synchrotron for dilute) | Catalysis, protein metal sites |

| XES | Secondary X-ray emission from core relaxation | Occupied electronic states, spin states | Bulk, element-specific | Coordination chemistry, bioinorganic |

| XRD | Constructive interference (Bragg’s law) | Crystal structure, lattice parameters | Full crystal volume | Protein crystallography, thin films |

| SEM-EDX | Electron imaging + EDX detection | Morphology + elemental distribution | Surface to few μm | Forensic particles, microstructure |

X-ray spectroscopy offers a versatile set of techniques that uncover matter’s atomic and electronic secrets. Methods like XPS reveal surface chemistry, EDX and SEM-EDX map elements in detail, XRF provides non-destructive bulk analysis, XAS and XES explore local states and XRD decodes crystal structures – together forming a powerful, multi-scale toolkit for intact samples.

In analytical chemistry, these tools pinpoint trace elements and shifts, from contaminants to reactions. In life sciences, they map enzyme cofactors, trace tissue distributions and decode biomolecules, boosting drug and disease research. They also shine in forensics, archaeology and environmental work.

Future innovations, like fourth-generation synchrotrons and portable XRF, enhance resolution and access, while machine learning simplifies data analysis, keeping X-ray spectroscopy key across science.

- Joseph I. Goldstein, Dale E. Newbury, Joseph R. Michael, Nicholas W.M. Ritchie, John Henry J. Scott DCJ. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis. 4th ed. Springer New York, NY; 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6676-9

- Leng Y. Materials Characterization: Introduction to Microscopic and Spectroscopic Methods. Wiley; 2013. doi: 10.1002/9783527670772.ch6

- Rupp B. Biomolecular Crystallography : Principles, Practice, and Application to Structural Biology. 1st ed. Garland Science New York, NY; 2009. doi: 10.1201/9780429258756

- Als-Nielsen J, McMorrow D. Elements of Modern X-Ray Physics. Wiley; 2011. doi: 10.1002/9781119998365

- X-Ray Data Booklet. https://xdb.lbl.gov/. Accessed September 22, 2025.

- Egdell RG, Bruton E. Henry Moseley, X-ray spectroscopy and the periodic table. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2020;378(2180):20190302. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2019.0302

- Ketenoglu D. A general overview and comparative interpretation on element‐specific X‐ray spectroscopy techniques: XPS, XAS, and XRS. X-Ray Spectrom. 2022;51(5-6):422-443. doi: 10.1002/xrs.3299

- Greczynski G, Hultman L. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Towards reliable binding energy referencing. Prog Mater Sci. 2020;107:100591. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.100591

- Pushie MJ, Pickering IJ, Korbas M, Hackett MJ, George GN. Elemental and chemically specific X-ray fluorescence imaging of biological systems. Chem Rev. 2014;114(17):8499-8541. doi: 10.1021/cr4007297

- Newbury DE, Ritchie NWM. Electron-excited X-ray microanalysis at low beam energy: Almost always an adventure! Microsc Microanal. 2016;22(4):735-753. doi: 10.1017/S1431927616011521

- Haschke M. Laboratory Micro-X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer Cham 2014;55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04864-2

- Janssens K, De Nolf W, Van Der Snickt G, et al. Recent trends in quantitative aspects of microscopic X-ray fluorescence analysis. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2010;29(6):464-478. doi: 10.1016/J.TRAC.2010.03.003

- De Groot F. High-resolution X-ray emission and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Chem Rev. 2001;101(6):1779-1808. doi: 10.1021/CR9900681

- Yano J, Yachandra VK. X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Photosynth Res. 2009;102(2):241-254. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9473-8