Addressing Development Challenges for RNA Therapeutics

Discover the breakthroughs that are transforming RNA molecules into versatile tools for combating diverse diseases.

When the concept of RNA interference was first introduced in the early 2000s, it raised the tantalizing possibility of using RNA molecules to modify human gene expression.1 Since then, a wide range of RNA molecules have been identified, and several RNA therapeutics have been approved with many more in development.1 Yet the road to approval for clinical application remains challenging for these biological molecules.

This article explores how challenges such as sequence optimization, immune activation and off-target effects are being addressed to enhance the safety, durability and efficacy of RNA therapeutics.

Types of RNA therapeutics

A growing understanding of RNA molecules and their roles in controlling gene activity and protein synthesis has led to a wide array of new treatment modalities. These range from short, antisense oligonucleotides, to more structurally complex RNA molecules, each optimized in different formulations for effective delivery.1

RNA molecules are by their nature short-lived, synthesized to perform a specific task and then degraded. To develop effective, safe and durable therapeutics, researchers need first to understand the cellular and tissue dynamics of RNA molecules in detail.

“For any given RNA, for example, encoding a viral spike protein, there are millions of potential different variants for the same spike protein, so the design space is almost infinite,” said Anne Willis, director of the MRC Toxicology Unit at the University of Cambridge. “Working out which is the most efficacious sequence for a therapeutic is challenging as it depends on so many variables.”

These include which tissue you want the therapeutic to target, how to select coding regions to give optimal translation elongation rates while preventing ribosome collisions along the mRNA, and choosing the best 5’ and 3’ untranslated region (UTR). These can all influence translation efficiency and protein stability and mitigate potential safety issues in different tissues.

Willis has been working with colleagues at the University of Kent on experiments to address such questions, such as determining the optimum 3’ UTR sequences in liver, muscle and brain and the decoding speeds of individual transfer RNAs (tRNAs). These data have been used to develop a computational algorithm that evaluates RNA sequences based on the desired properties of the resulting RNA and generates a shortlist of RNA sequences that can be explored experimentally.

“We performed a head-to-head comparison with the design strategy of an existing mRNA vaccine and found that our sequence gives a 20-fold better B-cell response and a five-fold increase in T-cell response,” explained Willis. “This means we could reduce the RNA dose in each vaccine, making it not only cheaper but also safer, by reducing effects intrinsic to RNAs like immunogenicity.”

A single RNA therapeutic for multiple diseases

Research underpinning the mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 had paved the way for new RNA therapeutic modalities to move from idea to reality. One example is the “basket approach”, in which multiple mRNAs are designed to cover viral evolution over time.

A similar approach is being used by Zoya Ignatova, director of the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Hamburg, who is developing suppressor tRNAs for rare monogenic disorders caused by nonsense mutations.

“In our case, the basket approach rather comes from developing a single entity to address multiple pathologies caused by multiple genes,” she explained.

Around 11% of all genetic diseases are caused by nonsense mutations and are usually connected with devastating phenotypes because the resulting proteins are not just misfolded but their translation is terminated entirely by the introduction of premature stop codons.2

Ignatova’s research focuses on designing variants of tRNAs that act as suppressor tRNAs and can specifically find those nonsense mutation-induced stop codons and restore protein synthesis.

“One of the problems with using an mRNA library replacement approach to monogenic diseases is the packaging capacity of the engineered non-toxic viruses used to deliver them,” said Ignatova. “Most genes that are usually mutated or linked to a genetic disease are very large and this hinders the ability of the virus to deliver them.”

By contrast, tRNAs are very small, usually between 70 and 90 nucleotides, and can be packaged easily. “Moreover, there are only three stop codons, so we can design a small set of suppressor tRNAs to be used for the same type of mutation across many different genes, and multiple diseases”.

However, care must be taken with designing suppressor tRNAs, because the nonsense mutation-induced stop codon is identical to the natural stop of every gene, and so off-target effects of suppressor tRNAs could potentially stop the termination of normal proteins, leading them to be mis-manufactured and misfolded.

Ignatova’s team has worked out how to manipulate tRNAs to prevent off-target effects and leave normal stop codons untouched3, “but this will have to be shown for every tRNA put on the market.” she cautioned.

Mitigating off-target effects

Off-target effects can be tissue-dependent too because, despite their uniform genetic information, tissues have very different concentrations of protein translation machinery components that may lead to toxicity in one tissue but none in another.

“We must measure the natural resources of the cell precisely, from the enzymes used to charge tRNAs with the amino acids to the ribosomal molecular machinery needed to synthesize the proteins,” said Ignatova. “If we are introducing something new, we try not to perturb this equilibrium in every cell.”

This also applies to RNA therapeutics beyond tRNAs. Willis’ team is exploring the idea of protein replacement therapy, but getting the product to the right tissue is essential.

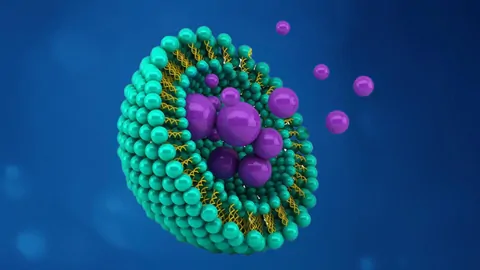

“In terms of delivery, if you need to replace a protein in the liver, that's really easy because lipid nanoparticles containing mRNAs will migrate to the liver anyway,” she said. “But if we want protein replacement in the heart and not in the liver, that's more of a challenge. There’s some fantastic research focusing on exploring new lipid-based particles and nanostructures that can target the cargo to the right organ.”

Other off-target effects can include unintentional changes to reading frames during protein translation, expression in non-target tissues, or blocking translation of essential proteins. Research from Willis’ team showed that certain modifications to mRNA vaccines can cause the ribosome to switch reading frames, or ‘frameshift’.4 “The off-target effect was surprising, but we know the sequence that causes a frameshift so it’s possible to modify the mRNA to take those sites out,” said Willis.

Immunogenicity

Immunogenicity is another common challenge in developing RNA therapeutics, because often when RNA is introduced into a cell, the cell thinks it is being attacked by a virus and triggers the innate immune response.

“Immunogenicity turns off protein synthesis, which is the one thing you're trying to achieve,” said Willis, “and it also induces inflammatory cytokines which, in the worst-case scenario, can result in a cytokine storm.”

Researchers commonly make modifications to RNA sequences to avoid this immunogenicity, but care is needed to avoid destroying the physiological structure and function of the RNA.5

“When we administer an already synthesized tRNA, the secondary structure of tRNA molecules usually helps decrease immunogenicity, and yet they can still be immunogenic,” explained Ignatova. “We have found positions in one or two places to introduce natural modifications that increase the efficacy of the tRNA and silence the immunogenicity completely.”

Future challenges

Despite rapid progress in this field, getting some of these innovative therapies to patients will require time and working closely with regulatory authorities.

For suppressor tRNAs, the challenges include conducting trials in such rare diseases and gathering preclinical evidence when few reliable models exist.

“Individual patient trials will really be the rolling stone in the whole process showing that it works and then we can start to recruit other patients with the same type of mutation,” said Ignatova. “Even two years ago, regulatory authorities weren’t prepared for this and would have required a standard clinical trial set up with a test arm. But now, they are moving forward with the field and endorsing models such as patient-derived materials (e.g., fibroblasts and epithelial cells) or induced pluripotent stem cells, which can provide disease models in a matter of months rather than years.”

For Willis’ field, one of the outstanding challenges is to understand the relationship between protein structure and translation and find the sweet spot between getting enough protein made with the desired rate of turnover.

“For certain structures, you want your protein to be translated quite slowly to ensure it folds correctly, especially for large molecules such as membrane proteins,” she said.

“We've worked on translation forever, so it’s nice to use that knowledge to translate the science and help others working in this area with diseases that we couldn't even think of treating before.”

References

1. Zhu Y, Zhu L, Wang X, Jin H. RNA-based therapeutics: an overview and prospectus. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(7):644. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05075-2

2. Coller J, Ignatova Z. tRNA therapeutics for genetic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024;23(2):108-125. doi: 10.1038/s41573-023-00829-9

3. Albers S, Allen EC, Bharti N, et al. Engineered tRNAs suppress nonsense mutations in cells and in vivo. Nature. 2023;618(7966):842-848. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06133-1

4. Mulroney TE, Pöyry T, Yam-Puc JC, et al. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2024;625(7993):189-194. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06800-3

5. Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23(2):165-175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008