What Is Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery?

Virtual screening can evaluate up to a billion molecules in a day, depending on computational power.

Virtual screening is a set of computational methods used to evaluate large numbers of molecules and identify those most likely to interact with a biological target, typically a protein. The concept is straightforward: a three-dimensional (3D) digital model of the target protein is used to test how well each small molecule might bind. Specialized software predicts these interactions using molecular docking, scoring functions or pharmacophore models to estimate binding strength and complementarity.1

Compared with experimental high-throughput screening (HTS), which can process up to about a million compounds per day, virtual screening can evaluate up to a billion molecules in a day, depending on computational power.2,3 This makes it far more cost-effective and allows for rapid iteration between design, prediction and refinement, thereby accelerating early drug discovery. While it does have limitations, such as dependence on the accuracy of the target model and potential false positives, virtual screening remains a highly valuable first step in identifying promising chemical starting points before committing to synthesis and experimental testing.4

What are the different types of virtual screening?

- Ligand-based virtual screening

- Structure-based virtual screening

- Hybrid methods

How does virtual screening work?

- Target research

- Binding site identification

- Model building

- Validation of the docking protocol

- Library preparation

- Molecular docking

- Pharmacophore mapping

- Scoring and ranking

- Compound selection and hit refinement

What are the different types of virtual screening?

Virtual screening can be approached in several ways, depending on whether the comparison is based on the known small molecule binders (ligands) or the target protein structure. Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) focuses on comparing new compounds to known active ligands. Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) focuses on how well compounds fit into a 3D model of the target protein. Both methods are often combined to improve accuracy.

Ligand-based virtual screening

Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) relies on known active compounds to identify new molecules that might act similarly.5 It is beneficial when the 3D structure of the protein target is unavailable or unreliable. The underlying principle is that molecules with similar chemical features tend to have similar biological effects. LBVS methods, such as molecular similarity searches, pharmacophore modeling or machine learning (ML), compare candidate molecules to known actives to identify likely binders. This approach is commonly used early in drug discovery to guide hit identification.

Structure-based virtual screening

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) uses the 3D structure of a target protein to predict how potential ligands might bind.4 This is done through molecular docking, in which each ligand is placed into the protein’s binding site in multiple orientations (poses), and the program estimates binding strength for each configuration. SBVS helps identify new binders, optimize leads and clarify how specific interactions drive molecular recognition – the selective binding of a ligand to a protein through complementary shapes, charges and hydrogen bonding patterns.

Hybrid methods

Hybrid methods combine LBVS and SBVS into one workflow.6 The ligand-based step can first filter a massive set of molecules to a smaller, more manageable subset, which is then docked against the protein structure. In some cases, both methods are integrated into the scoring process. This combined strategy enhances accuracy and efficiency, thereby increasing the likelihood of identifying genuine drug candidates.

How does virtual screening work?

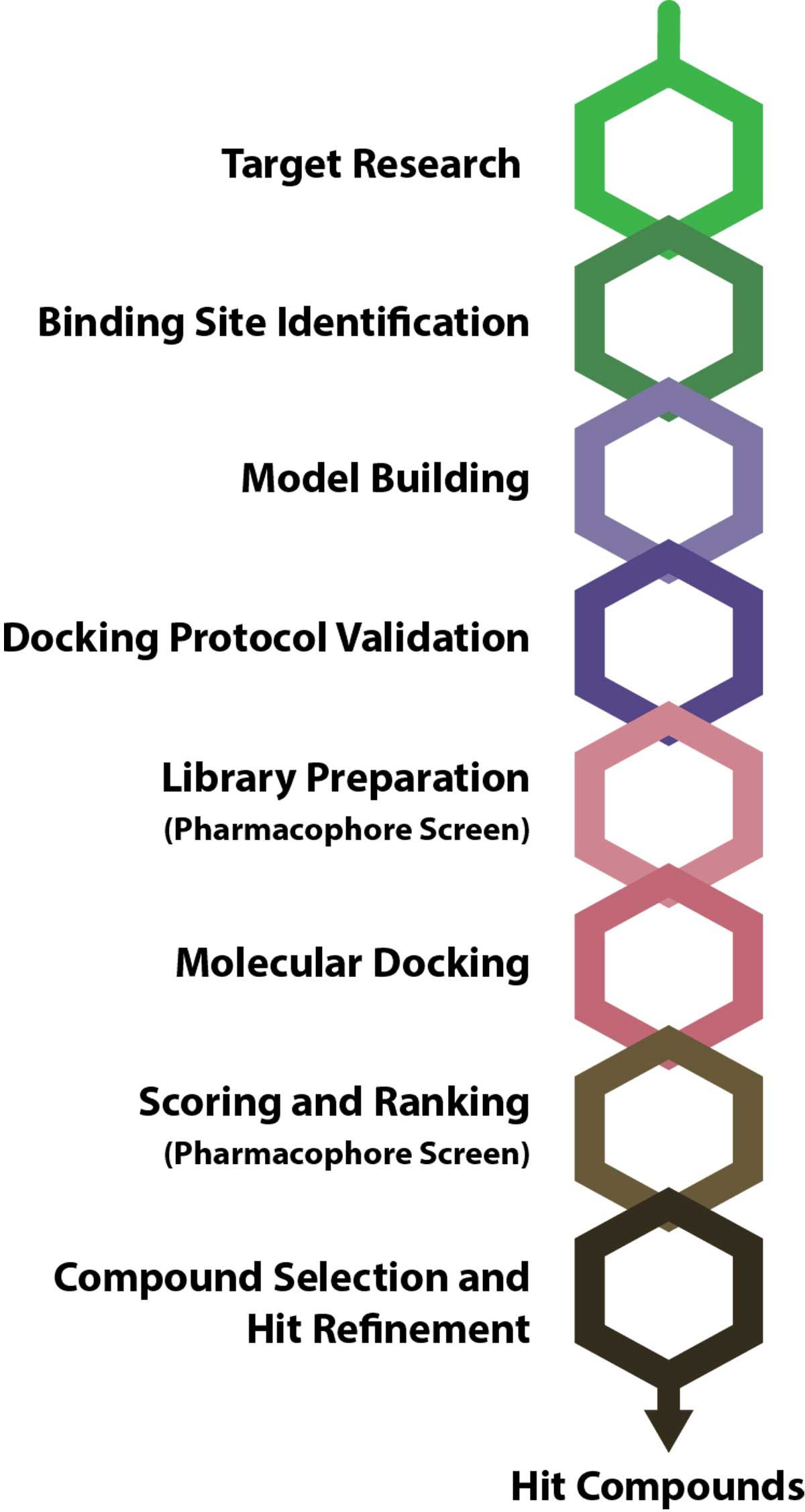

Virtual screening typically involves several key steps that underpin its accuracy and progressively narrow an extensive compound library to the most promising hits (Figure 1). These steps are described below.

Figure 1: Typical virtual screening pipeline. Pharmacophore screening can be integrated during library preparation or scoring and ranking. Credit: Technology Networks.

1. Target research

Selecting a valid biological target is one of the most critical steps in drug discovery. Because most diseases involve complex pathways, target validation increases the likelihood that modulating a specific protein will provide a therapeutic benefit. This process uses data from genetics, physiology, pharmacology, prior clinical studies and structural biology. For SBVS, having a high-resolution 3D structure of the target is especially important, as prediction accuracy depends directly on model quality.

2. Binding site identification

In SBVS, identifying the binding site is also critical.4 If the structure of a known ligand bound to the target exists, the binding site can be defined directly. Otherwise, computational tools such as geometry-based pocket detection, energy mapping or molecular dynamics simulations are used to locate likely binding regions. Once identified, the site is analyzed for its size, shape, hydrophobicity, charge distribution and flexibility to guide docking setup and improve accuracy.

3. Model building

Protein structures used in virtual screening are obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.7 When experimental structures are unavailable, homology modeling can be used to construct a model based on known structures of similar proteins, even from other species. Although less accurate than direct experimental structures, it can provide a workable approximation for computational studies. More recently, artificial intelligence (AI)-based protein structure prediction methods, such as AlphaFold, have emerged as valuable tools, offering high-quality models when no experimental data are available.8

Regardless of how the model is obtained, it must be carefully evaluated and prepared before docking. This involves verifying the accuracy of the amino acid residues, ensuring the binding pocket is well defined and performing standard preparation steps, such as removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, assigning proper charges and adjusting side-chain orientations. Once these refinements are complete, the protein model is ready for virtual screening.

4. Validation of the docking protocol

Before screening, the docking setup should be validated. One common test is re-docking a known ligand to confirm the algorithm can reproduce its experimental pose. Another is enrichment testing, which ensures that known active compounds rank higher than inactive “decoys”. These steps confirm that the virtual screen can distinguish true binders from non-binders. 4

5. Library preparation

A library is a virtual collection of compounds used for screening, which will be compared to known ligands in LBVS or docked to the target in SBVS. Libraries can originate from several sources: established commercial or academic screening sets, proprietary collections built around specific molecular scaffolds or combinatorial libraries generated by systematically combining chemical building blocks to explore vast chemical space. Depending on the application, libraries may range from hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds, with some ultra-large virtual libraries comprising billions of molecules.9

Before screening, ligands must be properly prepared to ensure accurate modeling. This typically involves minimizing geometry to relieve structural strain and adding hydrogen atoms and appropriate charges. Library curation may also include applying drug-likeness filters, such as Lipinski’s Rule of Five, to exclude unstable or non-drug-like molecules.10

6. Molecular docking

In SBVS, docking is used to predict how a small molecule will bind to a target protein. Docking estimates the binding pose, orientation and affinity of each ligand. The process typically involves generating multiple ligand conformations and systematically placing them within the protein’s binding site to identify the most energetically favorable interactions.

Docking can be performed using different approaches. In rigid docking, both the ligand and the protein are treated as fixed structures, which simplifies computation but ignores the natural flexibility of molecules. Flexible docking, by contrast, allows rotation of ligand bonds and, in some cases, limited movement of the protein side chains, producing more realistic binding predictions and improved scoring accuracy.

Several well-established software platforms are commonly used for docking studies. AutoDock and its optimized version, AutoDock Vina, are some examples of widely used open-source tools.11

7. Pharmacophore mapping

When no reliable protein structure is available, pharmacophore mapping provides an alternative. This approach identifies the key chemical features shared among known active compounds and represents them as a simplified 3D model. The model is then used to screen large compound databases for new molecules that share the same spatial arrangement of features.12

The process involved building the pharmacophore model, validating it against inactive compounds and utilizing it to identify new hits. This method is computationally faster than docking and is often used as an initial filter before further analysis.

8. Scoring and ranking

After docking or pharmacophore screening, compounds are scored and ranked according to their predicted binding strength. There are four main types of scoring functions used in molecular docking.13 Force-field–based scoring functions rely on physics to calculate interaction energies, such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions. Empirical scoring functions estimate binding strength not by relying purely on physics, but by summing different interaction energies, each weighted according to its importance determined from experimental binding data. Knowledge-based scoring functions rely on statistical analyses of known protein–ligand complexes to determine which types of interactions are most favorable. Finally, ML–based scoring functions use large datasets of experimental results to train predictive models that estimate binding affinity with higher accuracy.

In pharmacophore modeling, scoring measures how well a compound’s features match the model’s 3D arrangement. The highest-scoring compounds are considered the best candidates for experimental validation.

9. Compound selection and hit refinement

After scoring, the top-ranking compounds are filtered for chemical diversity, structural plausibility and drug-like properties. Visual inspection ensures realistic binding poses and good shape complementarity. Post-processing steps, such as in silico ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) prediction, help eliminate poor candidates.6 The remaining compounds with favorable binding, stability and safety profiles are advanced for further analysis through rescoring, molecular dynamics or experimental validation.

Benefits of virtual screening

Virtual in silico screening offers substantial advantages compared to traditional in vitro HTS (Table 1). First and foremost, it dramatically accelerates the evaluation of large numbers of compounds at a much lower cost and with greater flexibility, thereby reducing the time and expense associated with early-stage screening.1 This efficiency enables faster iteration cycles, meaning medicinal chemists can redesign and test ideas more rapidly. Furthermore, virtual screening unlocks access to extensive libraries of molecules, including compounds that haven’t yet been synthesized, which expands the chance of discovering novel chemotypes (structurally distinct molecules), beyond what’s available in physical screening collections.

Harnessing this capability means promising candidates can be identified before committing to synthesis or biological assays, which saves both time and money. Virtual screening is also highly versatile. It works even when structural information is limited, and it can be combined with other computational methods, such as QSAR (quantitative structure-activity relationship), molecular dynamics simulations and ML/AI, to refine predictions and enhance accuracy.14

Many approved drugs have benefited from or originated from early discovery work that used virtual screening. Some notable examples include dorzolamide, zanamivir, captopril and the HIV drugs ritonavir, saquinavir and indinavir.4 Another example is S-217622, a SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor that came from a virtual screen followed by a biological screen and a structure-based drug design optimization campaign that eventually resulted in approval in Japan.15

Nevertheless, virtual screening is not without its drawbacks. Because it relies on computational models and assumptions, it can suffer from false positives (compounds predicted to bind but that don’t) or false negatives (genuinely active compounds that are missed) due to limitations in the library, model or target representation. Additionally, the lack of physical testing means that many downstream issues, such as solubility, metabolism, toxicity and off-target effects, may remain hidden until later stages. And while virtual screening can suggest novel scaffolds, much of drug success still traces back to compounds found by HTS or experimental screening. For example, one large review found that only ~1% of clinical candidates originated from virtual screening alone, compared to more than 90% from traditional methods, highlighting that virtual screening is, for now, complementary rather than a replacement.16

Table 1: A summary of the pros and cons of different screening methods.

| Method | Pros | Cons |

| Physical HTS | Direct measurement, little model bias | Very costly; time-consuming; limited to molecules on hand |

| Virtual Screening | Low cost; fast; large library access; more novel chemotypes | Model dependent; risk of false positives/negatives; limited in addressing ADMET and dynamics |

AI-accelerated virtual screening tools

AI/ML is rapidly becoming a key tool in virtual screening. Traditional virtual screening often employs rigid rules or physics-based models to evaluate numerous compounds, but these methods can struggle with scale, complexity and accuracy. AI helps in three significant ways. First, it can pre-filter very large compound libraries, narrowing millions or billions of candidates down to a manageable set of high-probability hits. Second, it can improve the scoring and ranking of how well each compound binds to a target by learning from large sets of known ligand-target data rather than relying purely on textbook physics. Third, it supports active-learning loops, in which the system identifies which compounds to test next, learns from those results and uses that feedback to refine predictions, thereby accelerating the hit-finding process.14,17 In one study, an AI-driven structure-based virtual screening platform evaluated billions of compounds and identified multiple active hits in under a week.18 In another massive empirical study covering 318 distinct targets, the authors demonstrated that a deep-learning structure-based virtual screening platform consistently identified novel bioactive compounds. It achieved hit rates of ~5–8% while screening only ~85 compounds per target, suggesting AI can drastically improve virtual screening and may replace the need for physical HTS one day.19

These successes demonstrate that AI is already transforming the way early-stage drug discovery is conducted. However, AI models are only as good as the data they’re trained on – high-quality, diverse and representative data is crucial.20 They also don’t eliminate the need for experimental testing; they prioritize compounds more effectively. Additionally, several challenges remain, including AI model interpretability, domain transfer (the extent to which it performs on entirely new targets) and integration with the rest of the drug discovery pipeline.21

Computational screening tools are continually improving and will continue to help identify new molecules that save and improve lives.

- Pinzi L, Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4331. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331

- Wildey MJ, Haunso A, Tudor M, Webb M, Connick JH. High-throughput screening. In: Macor JE, ed. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol 50. Elsevier; 2017:149-195. doi: 10.1016/bs.armc.2017.08.004

- Acharya A, Agarwal R, Baker MB, et al. Supercomputer-based ensemble docking drug discovery pipeline with application to COVID-19. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60(12):5832-5852. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c01010

- Maia EHB, Assis LC, de Oliveira TA, et al. Structure-based virtual screening: from classical to artificial intelligence. Front Chem. 2020;8:343. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00343

- Lavecchia A, Di Giovanni C. Virtual screening strategies in drug discovery: a critical review. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(23):2839-2860. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990001

- Vázquez J, López M, Gibert E, Herrero E, Luque FJ. Merging ligand-based and structure-based methods in drug discovery: an overview of combined virtual screening approaches. Molecules. 2020;25(20):4723. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204723

- Wang HW, Wang JW. How cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography complement each other. Protein Sci. 2017;26(1):32-39. doi: 10.1002/pro.3022

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873):583-589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

- Sadybekov AA, Sadybekov AV, Liu Y, et al. Synthon-based ligand discovery in virtual libraries of over 11 billion compounds. Nature. 2022;601:452-459. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04220-9

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1-3):3-26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455-461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334

- Yang SY. Pharmacophore modeling and applications in drug discovery: challenges and recent advances. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15(11-12):444-450. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.03.013

- Li J, Fu A, Zhang L. An overview of scoring functions used for protein-ligand interactions in molecular docking. Interdiscip Sci. 2019;11(2):320-328. doi: 10.1007/s12539-019-00327-w

- de Oliveira TA, da Silva MP, Maia EHB, da Silva AM, Taranto AG. Virtual screening algorithms in drug discovery: a review focused on machine and deep learning methods. Drugs Drug Candidates. 2023;2(2):311-334. doi: 10.3390/ddc2020017

- Unoh Y, Uehara S, Nakahara K, et al. Discovery of S-217622, a noncovalent oral SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitor clinical candidate for treating COVID-19. J Med Chem. 2022;65(9):6499-6512. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00117

- Brown DG. An analysis of successful hit-to-clinical candidate pairs. J Med Chem. 2023;66(11):7101-7139. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00521

- Gentile, F., Yaacoub, J.C., Gleave, J. et al. Artificial intelligence–enabled virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries with deep docking. Nat Protoc. 17, 672–697 (2022). doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00659-2

- Zhou G, Rusnac DV, Park H, et al. An artificial intelligence accelerated virtual screening platform for drug discovery. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7761. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52061-7

- The Atomwise AIMS Program. AI is a viable alternative to high throughput screening: a 318-target study. Sci Rep. 14, 7526 (2024). doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-54655-z

- Chong A, Phua SX, Xiao Y, Ng WY, Li HY, Goh WWB. Establishing the foundations for a data-centric AI approach for virtual drug screening through a systematic assessment of the properties of chemical data. eLife. 2024;13:RP97821. doi: 10.7554/eLife.97821.2

- Ferreira FJN, Carneiro AS. AI-driven drug discovery: a comprehensive review. ACS Omega. 2025;10(23):23889-23903. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.5c00549