Navigating the Modern Proteomics Workflow: Key Technical Considerations

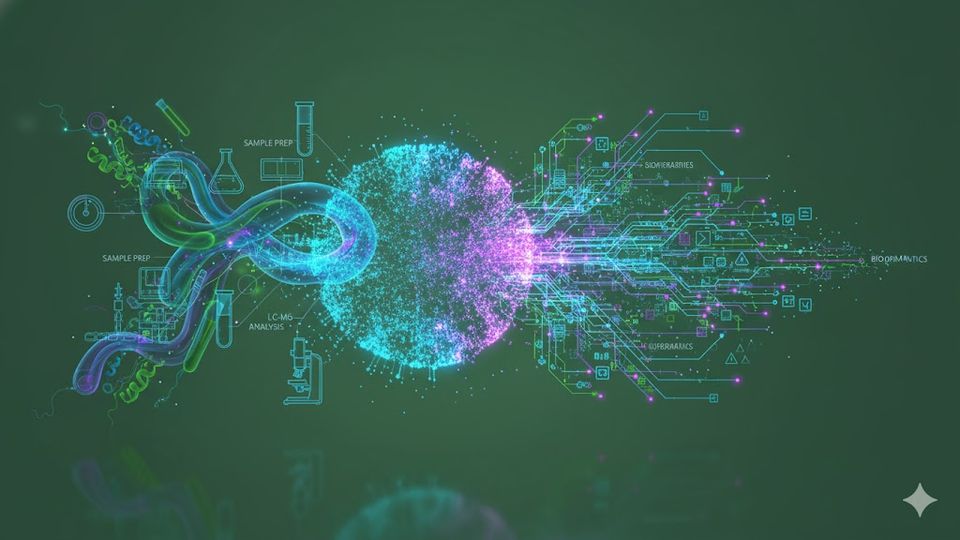

Protein analysis success requires optimization of the proteomics workflow across chemistry, LC-MS, and bioinformatics.

The proteome is defined by its inherent complexity, which includes dynamic post-translational modifications and vast concentration ranges. This dynamic nature necessitates a highly robust and standardized proteomics workflow. This end-to-end analytical proteomics pipeline is critical for converting intricate biological samples into quantifiable and interpretable data. It underpins advances in biomarker discovery, drug mechanism studies, and fundamental life science research. Maintaining high data quality and reproducibility throughout this process is essential. It demands a technical understanding of each step, from initial lysis and reduction to sophisticated bioinformatics. For laboratory scientists, optimization of the analytical process ensures the integrity of the results, providing confidence in conclusions drawn from protein expression profiles.

Sample preparation strategies for the proteomics workflow

The success of any large-scale proteomics study is fundamentally determined at the sample preparation stage, which serves as the critical bridge between the biological system and the analytical instrument. Poor quality or inconsistent sample handling inevitably introduces significant analytical noise, compromising downstream data accuracy. The primary objectives of this stage are twofold: to efficiently solubilize and extract all target proteins from the matrix (cells, tissue, or biofluids) and to prepare them in a format compatible with mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

Extraction methods must be tailored to the sample type, balancing the need for efficient lysis with the preservation of protein modifications and integrity. For cellular samples, techniques range from mechanical disruption to detergent-based lysis, where the choice of detergent (e.g., non-ionic or ionic detergents) dictates the efficiency of membrane protein solubilization versus the potential for ion suppression in the subsequent liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) step. Following extraction, a mandatory step in bottom-up proteomics (a strategy where proteins are digested into peptides before analysis) is protein digestion. This involves reducing disulfide bonds (typically with dithiothreitol or TCEP), alkylating free thiols (commonly with iodoacetamide) to prevent reformation, and finally, enzymatic cleavage. Trypsin is the most widely used enzyme due to its high specificity, which yields peptides suitable for MS fragmentation and database searching.

A crucial technique within the proteomics workflow for overcoming sample complexity and enhancing the detection of low-abundance proteins is fractionation. This can be performed at the protein level (e.g., using SDS-PAGE or IEF) or, more commonly in quantitative proteomics, at the peptide level (e.g., high-pH reverse-phase fractionation or strong-cation exchange). Fractionation effectively reduces the co-elution of numerous peptides, increasing the peak capacity of the chromatography system and allowing the mass spectrometer to spend more time sampling rare ions. This strategic application of pre-separation is a vital component of the proteomics pipeline and directly impacts the depth of proteome coverage achieved. The selection of sample preparation protocols must therefore be meticulously documented and rigorously standardized to ensure the reproducibility required for high-impact translational research.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and the quantitative workflow

The detection and quantification of peptides represent the core analytical phase, executed via the LC-MS workflow. This phase leverages the synergistic capabilities of high-performance liquid chromatography (LC) for peptide separation and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) for peptide identification and quantification.

The LC component, typically utilizing nano-flow reverse-phase chromatography, serves to separate the complex peptide mixture based on physicochemical properties, primarily hydrophobicity. Chromatographic parameters—such as column dimensions, stationary phase material, and gradient steepness—are highly influential. Longer columns and shallower gradients increase peak resolution and separation time, which is essential for maximizing protein identification in discovery experiments. The separated peptides are eluted directly into the mass spectrometer via an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (a technique that gently transfers ions from liquid into the gas phase).

Inside the mass spectrometer, peptides are ionized, accelerated, and analyzed. Modern proteomics relies heavily on high-resolution, high-mass-accuracy instruments, often utilizing high-resolution mass analyzers or time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers (devices that precisely measure ion mass based on flight time). The fundamental measurement in MS is the mass-to-charge ratio (

Quantitative methods further refine the LC-MS workflow. Label-free quantification (LFQ) methods (quantifying proteins by comparing signal intensity across different LC-MS runs) compare peptide signal intensities across different runs. Conversely, isobaric tagging methods (which chemically attach mass-balanced labels to peptides for multiplexing) chemically label peptides, allowing multiple samples to be multiplexed and run together. These labels yield reporter ions upon fragmentation, enabling the simultaneous relative quantification of peptides from up to 18 distinct biological conditions in a single proteomics pipeline run, significantly enhancing sample throughput and minimizing inter-run variation. Rigorous system suitability testing and quality control metrics are paramount throughout the LC-MS analysis to monitor retention time stability, mass accuracy, and spectral quality.

Table 1. Overview of key steps and technical considerations in the quantitative proteomics workflow.

| Workflow Stage | Primary Goal | Key Technical Consideration | Impact on Data Quality |

| Extraction | Solubilization of target proteins | Choice of lysis buffer and detergent | Maximize yield; minimize bias toward specific protein classes. |

| Digestion | Creating MS-compatible peptides | Enzyme specificity, incubation time/temperature | Generate reproducible, identifiable peptide fragments. |

| Fractionation | Reducing sample complexity | Number of fractions, pH gradient stability | Increase coverage of low-abundance proteins (depth). |

| LC Separation | Peptide isolation in time | Column length, flow rate, gradient steepness | Improve resolution; increase mass spectrometer duty cycle. |

| MS Analysis | Identification and Quantification | Mass accuracy, fragmentation energy settings | Ensure unambiguous peptide identification and precise quantification. |

Data processing, bioinformatics, and reporting standards

The transition from raw mass spectrometer output files (e.g., .raw, .mzML) to biologically meaningful conclusions is managed by the data processing and bioinformatics stage. This phase is arguably the most complex, requiring robust computational tools to interpret the vast volume of spectral data generated by the proteomics workflow.

The initial steps of data processing involve spectral pre-processing, including peak detection, mass recalibration, and feature alignment across multiple experimental runs, particularly for LFQ studies. Following this, protein identification is performed by searching the fragment spectra against a reference protein sequence database (e.g., UniProt) using search engines. Statistical validation is applied to these results to control the false discovery rate (FDR) (the expected proportion of identified peptides or proteins that are incorrect), commonly set at <

The crucial next step is quantification, which determines the relative or absolute abundance of the identified proteins across samples. For LFQ, this involves aligning retention times and calculating feature intensities, while for isobaric tagging methods, it involves extracting the intensities of the isobaric reporter ions. Downstream bioinformatics focuses on transforming the raw quantitative data into actionable biological knowledge. This typically includes statistical hypothesis testing (e.g., t-tests or ANOVA) to identify differentially expressed proteins, followed by functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, pathway analysis) to interpret the biological context of the findings.

Finally, adherence to reporting standards is essential for ensuring the transparency and reproducibility of proteomics data, which is a growing requirement for publication and data sharing in the life sciences. The community-defined Minimum Information About a Proteomics Experiment (MIAPE) guidelines (standardized reporting requirements for proteomics data) dictate the necessary metadata that must accompany any submitted dataset. This includes detailed information on sample preparation, instrument settings of the LC-MS workflow, and all parameters used during data processing. Adoption of standardized data formats (e.g., mzIdentML, mzQuantML) facilitates the deposition of data into public repositories, such as ProteomeXchange, allowing other researchers to validate and re-analyze the results, thereby reinforcing the overall scientific rigor of the proteomics pipeline.

Future directions in the proteomics pipeline

The contemporary proteomics workflow continues to evolve, driven by demands for greater sensitivity, speed, and proteome coverage. Advances in the LC-MS workflow, such as trapped ion mobility spectrometry (TIMS) and advanced data-independent acquisition (DIA) strategies, are transforming the field by offering enhanced separation dimensionality and more comprehensive peptide quantification. These technological leaps necessitate the concurrent development of sophisticated data processing algorithms capable of extracting quantitative information from increasingly complex spectral datasets. Moving forward, the emphasis will continue to be placed on standardization of sample preparation and robust adherence to reporting standards to ensure data interoperability. The seamless integration of high-throughput instrumentation with advanced computational strategies will solidify the proteomics pipeline as a central tool in biological discovery and precision medicine.

This content includes text that has been created with the assistance of generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing. Technology Networks’ AI policy can be found here.