Harnessing Cell Lines To Advance Cancer Research and Treatment

Cell engineering is transforming our understanding of cancer and paving the way for tailored treatments.

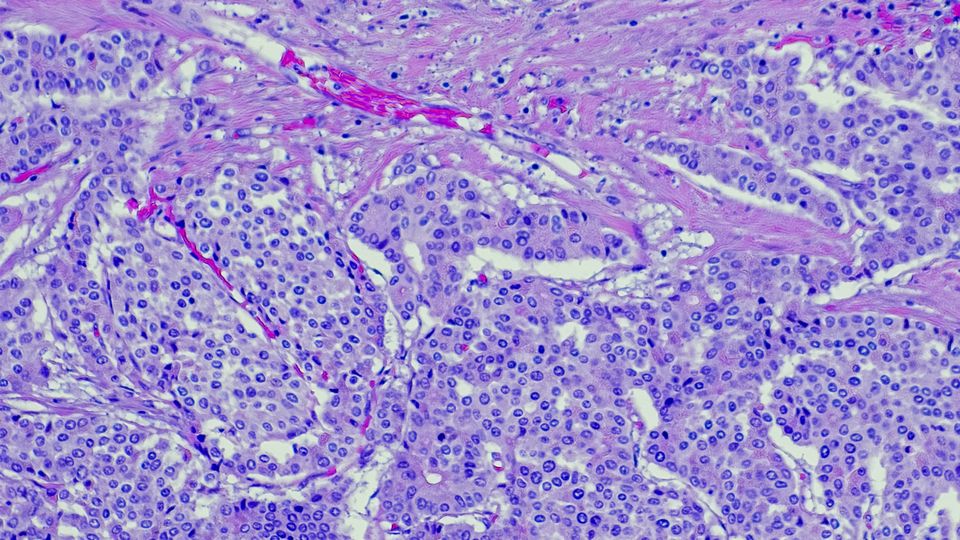

Genetic variation affects the expression of genes and function of proteins. DNA sequencing technologies have uncovered millions of genetic changes associated with various human traits and disease. However, it is still largely unclear which of these changes are harmful and how they cause problems. Efforts to understand the effects of gene variants in cancer cell lines are shedding light on cancer biology and drug resistance, and are paving the way for personalized therapies.

This article examines some of the cell-based approaches that researchers are using to study acquired drug resistance and the effects of specific genetic variants on cancer cell physiology. It also explores some of the challenges associated with working with cells, whether as model systems or for the production of biotherapeutics, focusing on the biological consequences of cell line engineering.

Developing cell lines to understand acquired drug resistance

Despite decades of medical advances, cancer is among the leading causes of death worldwide. A significant challenge in improving patient outcomes, particularly of those with metastatic disease, is the development of drug resistance.

Cancers that initially respond to treatment can later recur in a resistant form. This is partly due to clonal evolution, a process through which cancer cells expand and diversify by accumulating mutations over time. As a result, even closely related tumor cells may respond differently to the same therapy. Moreover, anti-cancer therapies exert selective pressure, accelerating clonal evolution processes and reducing the efficacy of treatment.

Studying resistance mechanisms in tumor tissue is challenging as it requires serial biopsies, which are invasive and often not feasible. The use of liquid biopsies has made monitoring cancer cell evolution easier, but translating this information into treatment decisions requires further research and clinical validation.

By growing cancer cells in the presence of anti-cancer drugs, Martin Michaelis, professor of molecular medicine at the University of Kent, aims to understand what makes certain cells resistant to specific drugs and what renders them vulnerable to others.

He has been looking after the Resistant Cancer Cell Line (RCCL) collection since the 80s. The collection, which originated in the laboratory of Jindrich Cinatl in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, now comprises over 3,000 cell lines.

The cells are continuously exposed to increasing anti-cancer drug concentrations to establish readily growing sub-lines that show a clear resistance to the selection agent. “Establishing a cell line resistant to classic cytotoxic chemotherapeutics can take over a year,” Michaelis said, “It is tough, expensive and labour intensive.”

Once the cells have acquired resistance to one drug, their response to other drugs can be tested. “We often find that cells that are resistant to one drug show collateral vulnerability that makes them more sensitive to other drugs,” he explained. Identifying biomarkers of these cells could eventually help guide treatment decisions.

Over 100 research groups in academia and industry are using the RCCL collection, applying omics methods to characterize cells in depth and develop novel therapies for patients who currently lack effective treatment options. A lot of work is being done to understand the rapid emergence of resistance to targeted therapies. For example, patients with melanomas that harbor the BRAF V600E mutation often respond very well to BRAF inhibitors initially. But, resistance emerges rapidly due to the development of compensatory mechanisms within the cells.

Combining BRAF inhibitors with MEK inhibitors, which target a related protein in the signaling pathway, can mitigate this rapid resistance.1 This is reflected in cell culture models where melanoma cells adapt to BRAF inhibitor therapy much faster than to traditional cytotoxic drugs.

Deciphering the mechanisms of resistance is no mean feat. Michaelis and others have shown that every resistance formation process is different. “If we take one cell line and adapt it to the same drug 10–20 times, we get 10–20 different phenotypes and drug resistance profiles,” he said. This diversity makes it crucial to generate so many cell lines and support the infrastructure required to maintain them.

High-throughput screening of cells with cancer-associated mutations

Another way to study cancer cell biology and intrinsic mechanisms of drug resistance, which are present before any treatment is administered, involves systematically knocking out or editing cancer-related genes. Gene-editing technologies are allowing researchers to introduce these mutations into cell lines and examine both their individual and combined effects on cancer progression, metastasis and response to therapies.

Francisco Sánchez-Rivera, assistant professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has been using prime editing, a refined version of CRISPR technology, to examine the effects of genetic variations on cancer cell growth and response to drugs. Prime editing enables any kind of point mutation to be introduced, as well as insertions and deletions, into the DNA of living cells without creating double-strand DNA breaks characteristic of traditional CRISPR-Cas9 methods. “With gene editing technologies, it is technically possible to understand the impact of every single gene variant in every single coding or non-coding region in the human genome,” he said. “We are just beginning to scratch the surface!”

His team has engineered over 1,000 variants of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, the most frequently mutated gene in cancer patients, to investigate their impact on lung adenocarcinoma cells. By using a high-throughput prime editing sensor strategy that couples prime editing guide RNAs with synthetic versions of their cognate target sites, they can quantitatively assess the effects of genetic variants found in patients on cell function at scale.2 Their work highlights the role of gene dosage in influencing the natural proportions of proteins and their interactions with each other.

Sanchez-Rivera is very enthusiastic about advances in the field. “With CRISPR-based technologies we can carry out experiments with remarkable precision and efficiency; they are already allowing us to model and dissect the aberrant circuitry of cancer cells.” Moreover, as sequencing technologies increasingly become integrated into clinical practice, this knowledge will help tailor therapies to patients with tumors that have a defined genetic makeup. “The next 5–10 years will be truly transformative,” he said.

Challenges of working with cell lines

In addition to the challenges associated with monitoring the viability of cells, optimizing growth conditions and avoiding contamination, the first major hurdles relate to the efficiency of introducing genetic material into cells (transfection) and controlling gene expression levels.

“We often have to test various delivery modalities, because different cell types are more or less amenable to transfection, and tweak and test different types of functional editing reporters to ensure that our cell line is capable of editing at very high efficiency,” Sanchez-Rivera explained.

His team recently experienced significant challenges trying to stably introduce cytosine and adenine base editors into mouse B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells using lentiviruses. To overcome this issue, they developed a strategy that couples stable viral guide RNA delivery and transient mRNA electroporation. Using this approach, they have produced single gene variant-based cellular models as well as multiplexed scalable mouse models in which thousands of genetic variants can be examined in vivo.3

When working with genetically engineered cells, it is important to consider the effect that the deleted, modified or new gene will have on cellular resources as this will influence the cells’ gene expression capacity. “Every time you engineer cells with genetic constructs, they draw on the cells’ enzymes, nucleotides and ribosomes to express them,” said synthetic biologist Francesca Ceroni. She and others have shown that the introduction of genetic constructs can impose an unintended “cost” or burden on mammalian cells.4, 5, 6

The diversion of cellular resources to transcribe and translate new genes can lead to slower growth rates and reduced expression, which can limit the production of biotherapeutics. Ceroni’s group based at Imperial College London focuses on characterizing the cellular burden caused by recombinant protein production and identifying design rules for synthetic systems to achieve robust control of gene expression. They are working in collaboration with several pharmaceutical companies to optimize the production of biotherapeutics.

Addressing resource competition and cellular burden is crucial for advancing cell engineering across various applications, including disease modeling, bioproduction and cell therapies. Ceroni calls for further research into the implications of resource competition in primary cells. “We need to further characterize the problem so that we can then develop tools to address it.” Approaches to precisely titrate the stoichiometry of gene expression in mammalian cells, such as the host-independent and programmable transcriptional system developed by Qin and colleagues that can improve the production of virus-like particles (VLPs),7 will contribute to improve the production of biotherapeutics.

“The toolkit for controlling gene expression is limited,” Ceroni said. By using machine learning to increase the design space, her team are testing new components and optimizing construct expression. When it comes to the production of biologics, this could be key to reducing costs.

She concluded by emphasizing the importance of a systems-thinking approach, especially when developing biotherapeutics. “You can’t only look at the cells, the interactions between different components of the process (cells, growth conditions, cell engineering) need to be carefully considered.”