Enhancing the Stability of Complex Cell Models

Alastair Carrington explains how hydrogel-based preservation technology supports the global distribution of sensitive biological materials.

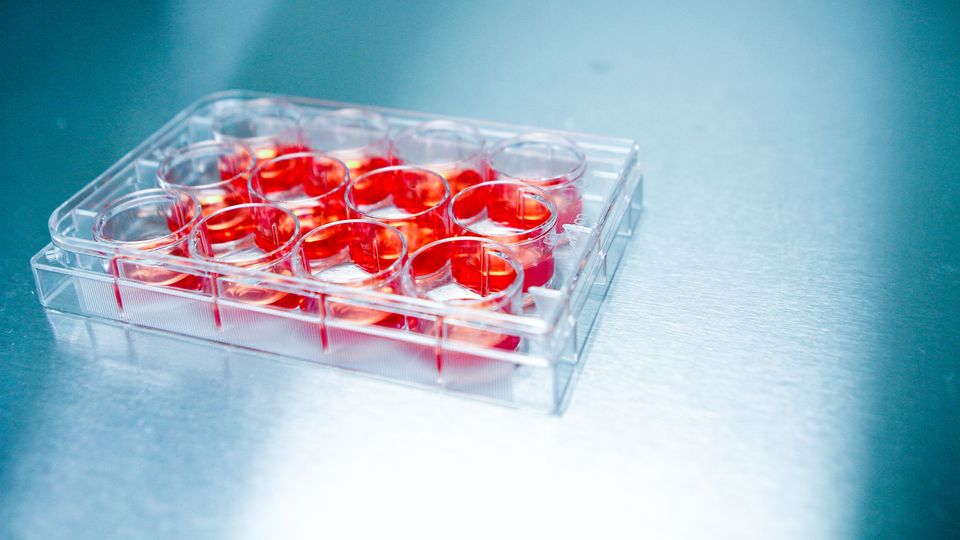

As the life science industry continues to adopt sophisticated in vitro models, new logistical challenges are emerging around the transport and preservation of complex cellular systems. Ensuring assay readiness, maintaining sample viability during transit and achieving standardization across geographically dispersed facilities are critical considerations for researchers and manufacturers.

At the recent ELRIG Drug Discovery conference, Technology Networks spoke with Alastair Carrington, director at Atelerix, to explore how the company’s hydrogel-based preservation technology addresses these hurdles. In this interview, Carrington outlines how the platform can enable greater workflow flexibility, lower shipping costs and support the global distribution of sensitive biological models.

Can you tell us about the cell models and biological systems that you've seen the most demand for, and how your technology supports this?

Probably one of the biggest trends in industry we're seeing is a movement away from animal models in preclinical research. What we're seeing is a lot of people doing in vitro assays, particularly in complex 3D models, organoids or spheroids. What we've observed is a need to standardize those models to enable them to be relevant for drug discovery and clinical trial research.

The problem with standardization is that it requires the same facility to generate those models and then be able to ship them globally to other facilities. Currently, it's incredibly difficult to ship those models. Typically, the more complex a model is, the worse it is, in terms of product preservation, as you can't really freeze it down. There are huge costs and risks associated with shipping those models around the globe, making them very expensive.

With our technology, we enable safe passage for models that are historically too sensitive or too complex to be shipped, enabling them to be transferred across collaborators.

Assay readiness is very difficult for most people to achieve at the moment, unless they look at the same site facility.

With our technology, we enable greater flexibility; you have up to two weeks to store samples at ambient temperature. Typically, a lab would receive a shipment from their collaborator. There would be a mad panic to ensure the model is processed, and the assay is still working. People have to stay late. Shipment anxiety is incredibly real.

With our technology, it removes all that anxiety because if it arrives late, it's fine. They can release cells or assays whenever they feel like it.

All of our products have been designed with scalability and automation in mind. Protocols have been developed to minimize the number of handling steps and solely rely on liquid handling and transfer processes. This makes them compatible with anything from small semi-automated liquid handlers for small batches, up to substantial automated platforms for larger bulk sizes.

Our products also enable flexibility in downstream manufacturing processes. Where processes such as freezing expose biosamples to toxic components and need to be transferred to controlled-rate freezers as soon as possible, our products enable encapsulated cells or assays to be held at room temperature until they are ready to be stored or dispatched.

We enable extremely minimal disruption to the sample, and that's incredibly important because as soon as you fix something, you change it by nature. As soon as you freeze something, there's a huge amount of stress introduced. No matter how delicately you do this, you change the makeup of that sample, including the cell, intracellular components and molecular composition.

Our technology puts the sample in a gentle, hibernated state, where metabolic activity is extremely low, which prevents disruption to future assays. We enable viability in the sample, as if it were taken fresh from the patient or from a supplier.

Particularly when you look at areas such as clinical trials. There's so much variability in the samples that people receive from patients. There’s up to 30% resampling for most patients who take part. Also, people can't reproduce those results and are not sure whether it’s artifacts of shipment or not.

There are a couple of features of the gel that enable this variability to be reduced. Being a gel, it is naturally very good at shipping. The actual mechanical shearing that you would experience if you used other technologies doesn't happen.

No, because what we do is enable that flexibility. It's actually the opposite – we provide people with the flexibility they need for high-throughput screening. At the start of their screening processes, pausing their workflows to enable cells to be held in a stable, hibernated state makes everything a lot easier for these users.

Particularly when you look at flow units, their volumes are absolutely huge. Talk to any manager of a flow unit; they're always the most stressed people. They always have too much to do. It's nice that we're able to enable them to receive samples at any time.

I think one of the biggest trends we see is global disruption. People are getting a bit antsy and looking at trials that they have planned in three to five years. How stable will the worldwide supply chains be to enable them to conduct those trials? We’re seeing trials that are closer to onshoring than we've seen previously.

We’re also seeing trials being set up at a higher rate in developing countries that haven't got the same kind of geopolitical influences as other nations. This leads to quite a large problem in terms of sample logistics. The ability to obtain samples from across regions is a real issue. Then, to deliver advanced therapies to the patients who have that condition is an issue, because unfortunately for pharmaceutical companies and researchers, everyone with the same illness doesn't live in the same village, so they have to be able to get these drugs or receive samples at various locations.

What we're seeing is a huge number of clinical sites, basically being pop-ups in these remote regions. A large amount of education and resources are required on site, rather than being able to take a sample, drop it into a vial like ours and then ship it back to the central laboratory. The cost of infrastructure around all that is phenomenal. We're talking about tens to hundreds of clinical sites set up to enable things to be processed, not to mention the natural logistics on the ground.

I think technologies like ours that enable people to distribute advanced therapies to patients across remote regions will see increased use, particularly as so many people are incentivized to continue to research rare diseases.

The introduction to this interview includes text that has been created with the assistance of generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing. Technology Networks' AI policy can be found here.