Engineering Immune Responses: Protein Design for the Next Era of Cancer Therapy

Protein-based therapies have surged since the 1980s. Yet they come with their own hurdles.

Speaking at Technology Networks’ “Landscape of Cancer Research: Advances in Immuno-oncology 2025” event, Dr. Jamie Spangler gave a keynote that set the tone: a vision of how engineered proteins could overcome the toughest challenges in cancer immunotherapy.

Spangler, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University, began by reminding the audience of an important reality: while proteins have revolutionized medicine, they weren’t built with drug developers in mind.

“Proteins in nature don’t care about your drug,” Spangler explained. “We take it as our mission to redesign what nature has given us – or create entirely new proteins that could be therapeutically useful.”

Her lab, she said, takes a three-pronged approach:

- Engineering cytokines and growth factors.

- Designing mechanism-driven antibodies.

- Developing discovery platforms for hard-to-target membrane proteins.

Why natural proteins struggle as medicines

Protein-based therapies have surged since the 1980s. Today, 7 of the 10 best-selling drugs worldwide are biologics, from monoclonal antibodies to receptor decoys. Yet, Spangler noted, natural proteins come with baggage:

- Pleiotropy: One molecule can activate multiple receptors or cell types, reducing precision.

- Off-target effects: Proteins often act in unintended tissues.

- Manufacturing challenges: Many proteins aggregate or become immunogenic when produced outside the body.

- Rapid clearance: “That very rapid clearance rate – often less than five minutes – makes the response transient and delivery inefficient,” she said.

Protein engineers, she argued, are tasked with re-shaping biology itself – improving stability, specificity and persistence so proteins can function as reliable medicines.

Reprogramming cytokines to bias the immune system

The first case study centered on interleukin-2 (IL-2), one of the earliest cytokines used as a cancer therapy. High-dose IL-2 can trigger complete, durable cures in a fraction of patients – but with life-threatening toxicity.

“IL-2 can be effective, even leading to cures,” Spangler said. “But patients often refuse therapy because of the very toxic side effects – vascular leak syndrome, organ failure, even death.”

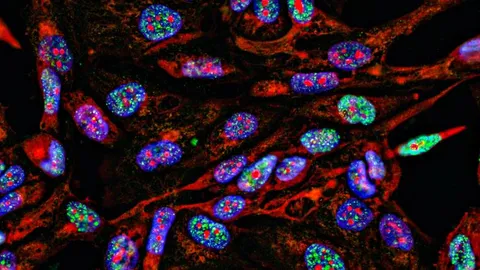

The problem lies in IL-2’s dual role: it stimulates both effector T cells (which attack tumors) and regulatory T cells (which suppress immunity). To fix this, Spangler’s team created antibody-cytokine fusions known as immunocytokines.

One design, the F10 immunocytokine, showed dramatic results. In mouse models, it biased IL-2 toward activating effector cells while sparing regulatory T cells. By further fusing the molecule to a collagen-binding domain, they ensured it localized to tumors and stayed put.

“We saw robust tumor retention with no off-target toxicity,” Spangler reported. “The molecule stuck in the tumor, while plain IL-2 escaped systemically.”

When combined with checkpoint inhibitors like anti-PD-1 antibodies, the approach produced synergistic survival benefits in both “cold” melanomas and “hot” colorectal cancers.

Multi-paratopic antibodies: beating tumors at their own game

The second prong of Spangler’s research focuses on antibody engineering. Traditional antibodies block interactions like PD-1/PD-L1, but tumors often find ways to recover.

Her lab designed multi-paratopic antibodies, which can bind to multiple non-overlapping sites on the same protein. This clustering induces receptor cross-linking and internalization, stripping key molecules like PD-L1 from the tumor cell surface.

“It’s like mowing the lawn,” Spangler said. “You can tarp the grass to block the rain – or you can cut the receptors off the surface so the ligand can’t bind in the first place.”

To expand binding diversity, her team turned to an unusual ally: nurse sharks. Sharks produce VNARs, compact single-domain antibodies that bind to small epitopes inaccessible to larger antibodies.

By combining VNARs with FDA-approved checkpoint antibodies like atezolizumab, Spangler’s group built tri-paratopic antibodies capable of both blocking PD-L1 and removing it from the tumor surface.

In vivo experiments confirmed that their lead candidate, TS1521, significantly reduced available PD-L1 in tumors and enhanced T cell reactivation.

“The shark antibodies gave us access to new binding sites,” Spangler explained.

“That allowed us to design multi-paratopic molecules with unprecedented potency.”

Biofloating: A platform for discovering the undiscoverable

The third innovation Spangler highlighted addressed a long-standing problem: antibody discovery against membrane proteins.

Though membrane proteins make up less than a quarter of the proteome, they account for 60% of approved drug targets. Yet very few antibodies target them, due to difficulties producing stable, purified proteins for discovery campaigns.

Spangler’s team developed biofloating, a solution-phase system that interfaces yeast libraries with live mammalian cells expressing the target protein.

“If you can’t bring the proteins to the cells, why not bring the whole cell to the system?” Spangler asked. “That’s what biofloating allows us to do.”

Compared to traditional “biopanning” methods, biofloating proved far more sensitive. It detected binders against both abundant and scarce receptors, enabling the discovery of nanobodies with nanomolar affinities against GPCRs like CXCR2. Importantly, some antibodies targeted unique epitopes untouched by existing drugs.

From discovery to the clinic: Hurdles ahead

Despite these promising advances, Spangler cautioned that moving molecules from the lab bench to clinical trials is fraught with barriers.

“The biggest challenges are money and bandwidth,” she said. “You either need to start your own company or license your molecule and hope the partner is committed to it.”

Industry collaborations, she emphasized, will be critical in bridging the so-called “valley of death” between preclinical work and clinical translation.

The future of protein engineering in oncology

For Spangler, the key to tackling cancer lies in combination therapies that harness multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

“Cancer is constantly a step ahead of us,” she reflected. “It would be naive to think one mechanism will cure it. These complex diseases are going to require complex cures.”

Her lab’s innovations – cytokine biasing, multi-paratopic antibodies and discovery platforms – illustrate how rational protein design can supply the next generation of tools for that fight.

“Ultimately,” she concluded, “our dream is to see how we’re actually doing in real time, and adjust through engineering to make molecules even better.”

This content includes text that has been generated with the assistance of AI. Technology Networks' AI policy can be found here.