An Introduction to Bioinformatics, Bioinformatics Tools and Applications

Bioinformatics provides the methods to store, analyze and interpret the complex datasets generated by modern research.

We are living in an era where biology has become synonymous with big data due to the ever-increasing amount of data being generated by technologies such as next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics provides the infrastructure, algorithms and analytical power to make sense of all this information, and its importance is felt across almost every aspect of modern life sciences, from personalized medicine to tracing the evolutionary history of life.

In this article, we will first introduce the field of bioinformatics and its importance as a cornerstone of biological research, then its history from the comparative analysis of the first amino acid sequences to the advent of high-throughput sequencing, before introducing some of the principal tools and techniques being used in bioinformatics today, such as BLAST, protein structure prediction and phylogenetics.

Why is bioinformatics analysis important?

Computational biology vs bioinformatics

Bioinformatician vs bioinformatics scientist – Is there a difference?

Bioinformatics tools and resources

- BLAST in bioinformatics

- ClustalW/ Clustal Omega

- Ensembl

- UniProt

- KEGG

- Bioconductor

- Biopython

The application of bioinformatics

- Multiple sequence alignment in bioinformatics

- GWAS

- Protein structure prediction

- Transcriptome analysis

- Gene expression analysis

- Phylogenetic analysis

What is bioinformatics?

Bioinformatics is a field of science that combines biology, computer science and information technology, and is critical for extracting meaning from biological data. It provides the methods and tools to store, analyze and interpret the massive, complex datasets now being generated by modern biological research. Bioinformatics takes the enormous volume of raw data being generated by sequencing and other techniques and transforms it into biological knowledge, leading to key insights into the world around us and medical breakthroughs.

Bioinformatics covers an increasingly broad range of analyses, but the most important areas include genomics (the analysis of entire genomes), transcriptomics (analyzing the RNA in a cell), proteomics (characterizing proteins) and metabolomics (profiling metabolic products). The development of these sub-fields means that bioinformatics now enables a global, systems-level approach to science, allowing scientists to move beyond studying single genes to understanding how networks of molecules interact at local (cells or organisms) or global scales (entire ecosystems).

Why is bioinformatics analysis important?

In the decades since the first human genome was published, the cost of sequencing a full human genome has gone from billions of dollars to close to one hundred dollars, meaning scientists can now sequence thousands of genomes, generating vast amounts of information. Without bioinformatics, the inundation of data from genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic datasets is impossible to navigate or understand, and its importance is now felt across almost every facet of the life sciences.

For instance, bioinformatics is helping drive the field of personalized medicine. By comparing a person’s genome to a reference database, bioinformaticians can identify genetic variants that may predict their susceptibility to diseases and response to certain drugs, thus helping tailor medical treatments to their genetic makeup. In drug discovery and development, bioinformatics is used to identify novel drug targets, design drugs that interact with these targets and then predict potential side effects.

Programs such as the Tree of Life1 at the Wellcome Sanger Institute are providing key insights into evolutionary and conservation biology. By sequencing the genomes of every species in Britain and eventually on Earth, the program will help improve the understanding of how species have evolved and inform conservation efforts for endangered species.

Bioinformatics definition

Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that develops and applies computational methods, including statistical models, algorithms and databases to analyze and interpret large-scale biological data with the goal of uncovering biological insights from datasets such as DNA sequences, protein structures and gene expression profiles.

History of bioinformatics

Bioinformatics was first defined by Hogewig and Hesper in 19702 as “the study of informatic processes in biotic systems”, although the foundations of what would become the field of bioinformatics were laid in the 1960s. One of the earliest combinations of computational and experimental approaches to understanding biological macromolecules was performed by Zuckerkandl and Pauling in 19653 when they compared known amino acid sequences for cytochrome c and hemoglobin from different species, counted the number of amino acid differences and compared these to times of evolutionary divergence estimated from the fossil record. Measuring sequence divergence forms the basis of the algorithms and statistical models used for phylogenetic tree inference.

The beginning of the 1970s saw the publication of the first sequence alignment algorithms4,5 and nucleotide substitution6 models, and in 1977, the first complete genome of any organism, the bacteriophage φX174, was sequenced using the dideoxy chain-termination method that would become known as Sanger Sequencing.7 The resulting increase in the amount of sequence data saw the release of tools that would become ubiquitous, such as the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST),8 which allowed public databases like GenBank9 to be searched quickly. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the usage of the term “bioinformatics” became mainly associated with the computational analysis of genome data, and the launch of the Human Genome Project in 1990 would come to define modern bioinformatics with its demand for the computational power, data storage and new algorithms that were required to assemble billions of DNA fragments.

Following the completion of the first draft of the human genome in 2003,10 bioinformatics began to move into the “omics” (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics etc.) era with the generation of ever larger datasets, helped by the development of increasingly high-throughput sequencing technologies such as 454 and Illumina. Since the late 2010s, the development of increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning models has seen a further revolution in bioinformatics, particularly in the fields of protein structure prediction and drug target discovery.

Computational biology vs bioinformatics

While bioinformatics is sometimes referred to as computational biology, there is generally considered to be a distinction between the two. Bioinformatics focuses on the development of algorithms, tools and databases and is concerned with the “how”. For instance, the design of novel algorithms to find genes in a genome or building a database to store protein–protein interactions. In comparison, computational biology is interested in the “what” and the “why” like what genes are involved in causing resistance to antimicrobial agents or why a particular mutation causes a disease. In practice, for many professionals, the distinction is blurry as they will often have to develop the tools before they can extract meaningful findings from their data.

Bioinformatician vs bioinformatics scientist – Is there a difference?

Generally, there is some fluidity and overlap in the definition of bioinformatician versus bioinformatics scientist. Broadly, a bioinformatician will be skilled at applying bioinformatics tools and workflows to analyze data without necessarily having a deeper understanding of how these tools work, whilst a bioinformatics scientist will be an expert in developing novel algorithms and designing new software with a very good understanding of their usage. Usually, most practitioners in bioinformatics will be bioinformaticians, with the number of bioinformatics scientists being quite small and more likely to occupy specialized roles within organizations.

FASTA in bioinformatics

The FASTA format is a standard text-based format for representing nucleotide or amino acid sequences and is the starting point for many bioinformatics tools, including BLAST and sequence alignment. A FASTA file consists of:

- A header line that begins with a “>” (greater than) symbol that contains information about the sequence, such as name, unique identifier or source organism

- One or more lines of sequence data using the standard International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) codes (A,T,C,G for DNA and A,B,C,D etc. for protein)

Bioinformatics tools and resources

There are a huge number of different software tools and databases used in bioinformatics, but these are some of the most important and widely used:

BLAST in bioinformatics

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)8 is an algorithm and tool that allows unknown DNA or protein sequences to be searched against massive online databases such as GenBank to find similar sequences. For instance, when a scientist identifies a novel gene in a mouse genome, the first thing they will do is to “BLAST” that gene’s sequence against GenBank to see if there are similar sequences in other species, such as humans. BLAST is available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website but can also be installed locally.

ClustalW/Clustal Omega

ClustalW11 and its more recent successor Clustal Omega12 are tools for performing multiple sequence alignment (MSA). MSA is the process of aligning three or more nucleotide or amino acid sequences to identify regions of similarity that may be conserved. These conserved regions may indicate important structural or functional relationships between different species. Performing MSA is often the first step in any comparative genomics study, and alignments form the basis of phylogenetic tree construction. Available as standalone tools, Clustal can also be used on the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) website.

Ensembl

Ensembl13 is a comprehensive, open-source online genome browser for vertebrate and, more recently, non-vertebrate genomes maintained by a dedicated team of curators. Currently, there are close to 500 species in the database, and it allows a scientist to enter a gene name or genomic location and obtain a range of information, such as its sequence, the transcripts it produces and homology to genes or regions in a variety of species in an intuitive visual interface.

UniProt

The definitive database for proteins, The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt),14 provides protein data curated from the scientific literature. For a given protein, UniProt will provide its sequence, known functions, domains and active sites as well as any associated diseases and its 3D structure if available.

KEGG

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)15 is a collection of databases for helping understand the high-level functions and utilities of a biological system. KEGG hosts a collection of pathway maps, which are graphical diagrams showing regulatory and metabolic pathways and molecular interactions. A scientist can provide a list of differentially expressed genes and KEGG will map them to pathways to identify whether any of the genes are enriched in a specific biological process.

Bioconductor

Based on the R programming language, Bioconductor16 is an open-source software project that provides more than 2,000 software packages for the analysis of high-throughput genomic data. Alongside packages for statistics, Bioconductor also includes packages for analyzing virtually every type of genomic data, including microarrays, cytometry and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data. Each package comes with a vignette, a document that provides a description of its functionality.

Biopython

Biopython17 is a library of open-source tools written in Python that simplifies common bioinformatics tasks. It provides pre-written, robustly tested code for a variety of tasks such as reading FASTA files, parsing BLAST outputs, translating DNA sequence into amino acid sequence and accessing online databases such as GenBank. This functionality means bioinformaticians can use the code provided by Biopython to perform necessary file operations quickly, which allows their analyses to be conducted.

The application of bioinformatics

Bioinformatics is a complex and ever-expanding field with many different applications. Here are some of the key ones:

Multiple sequence alignment in bioinformatics

MSA is the process of aligning three or more nucleotide or amino acid sequences and there are several different uses for it. These include identifying conserved residues that determine which parts of a protein are essential for its functions, generating high-quality sequence alignments to use to build phylogenetic trees and aligning sequences from different species to help design primers that can be used to amplify genomic regions using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

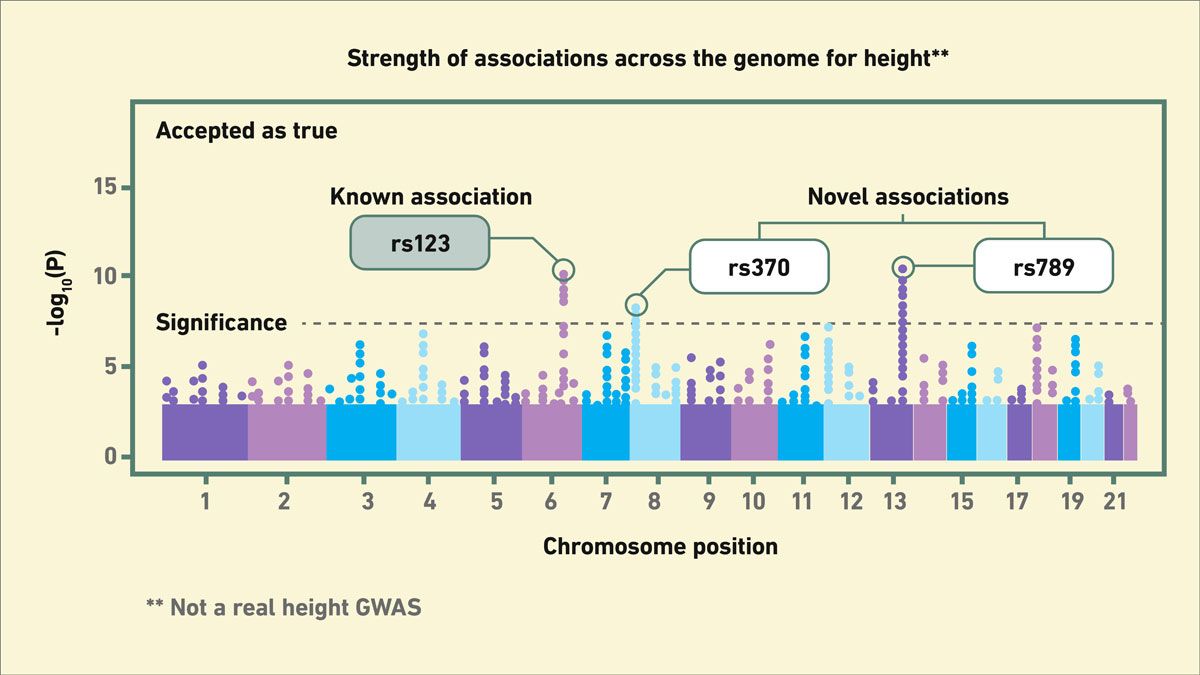

GWAS

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) is a powerful statistical approach for identifying genetic variants associated with a specific trait or phenotype, such as a disease. To do this, genotypes, usually in the form of hundreds or thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are extracted from the genomes of healthy (controls) and sick (cases) people. Sophisticated algorithms are then used to identify SNPs that are more frequently found (associated) in people with the disease compared to healthy people (Figure 1). Once identified and validated functionally, these variants can then be used as a predictive or diagnostic test.

Figure 1: Example of a Manhattan plot for GWAS. Credit: Technology Networks.

Protein structure prediction

Predicting protein structure from its amino acid sequence is vital for understanding protein function and for drug design, as many drugs work by binding to a specific part of a protein. Until recently, this was a costly, slow and challenging process. However, the development of AlphaFold218 by DeepMind, which uses machine learning and AI to predict protein structure, has revolutionized the field by achieving unprecedented accuracy.

Transcriptome analysis

Transcriptome analysis involves analyzing all the RNA molecules in a cell, typically with RNA-seq to get a snapshot of gene transcription at that moment in time. Short sequence reads are aligned to a reference genome, and the number of reads mapping to each gene are counted, with the idea being that the more reads that map to a gene, the more that gene is being transcribed in that cell. Gene transcription profiles are usually generated for different conditions, e.g., healthy versus diseased tissue to identify genes that are being differentially transcribed (see below).

Gene expression analysis

This is the outcome of transcriptome analysis. Bioinformaticians use Bioconductor packages such as DESeq219 and edgeR20 to normalize read counts and perform rigorous statistical testing to identify genes whose expression has significantly changed. While this identifies transcriptional activity, it is important to consider how much of this RNA is eventually translated into proteins, as not all transcripts lead to functional protein products. Combining transcriptome data with proteomics or ribosome profiling provides a more complete picture of cellular activity and can help better explain how biological processes, such as how cells respond to stimuli or tissue differentiation, are regulated at both the RNA and protein level.

Phylogenetic analysis

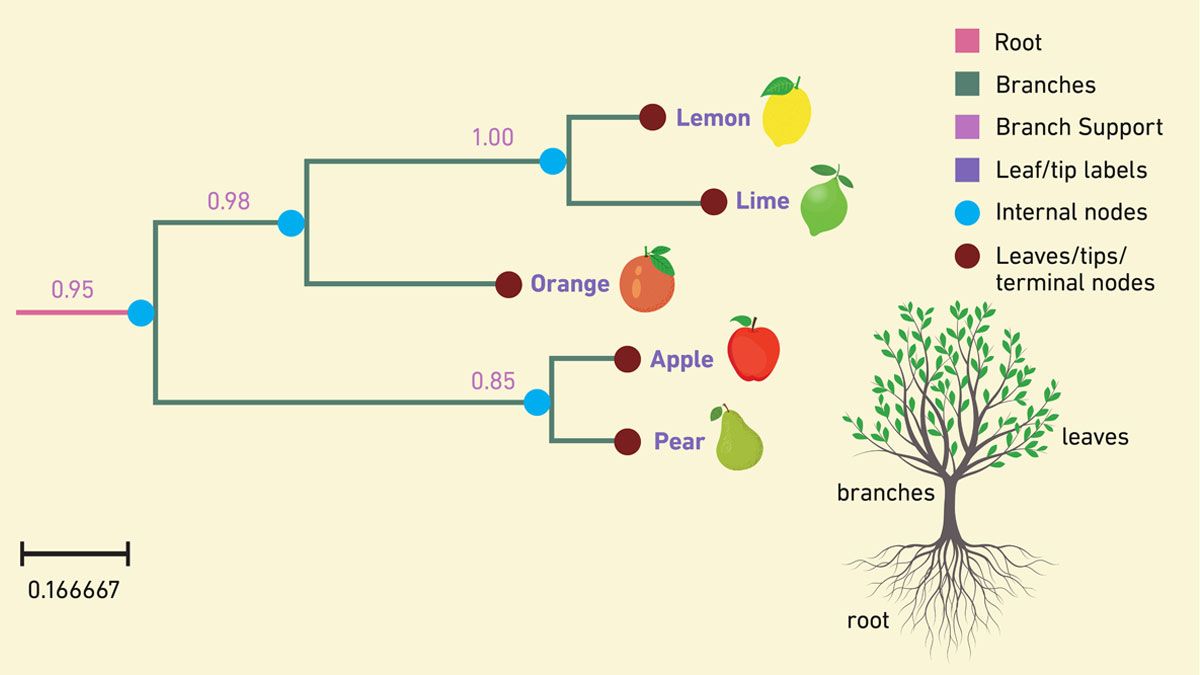

Phylogenetic analysis is used to help scientists understand the evolutionary relationships between different organisms using traits such as DNA or amino acid sequences or morphology. The result is a phylogenetic tree, a type of graph structure or family tree, which depicts the hypothetical relationships and inferred evolutionary history between the organisms (Figure 2). These trees can be used to map the history of life on Earth, trace the origin of pathogens at local or global scales and track the evolution of antibiotic resistance.

Figure 2: Example of a phylogenetic tree with the component parts indicated. Credit: Technology Networks.

Summary

Without the infrastructure and analytic techniques provided by bioinformatics, we would have no way of making use of the huge volumes of biological data being generated daily. In this article, we explored the foundational concepts of bioinformatics, from its history and key terminologies to the practical toolbox of modern bioinformaticians. Looking ahead, the rapid advancements in AI and machine learning are transforming how bioinformatics is done. From speeding up coding to rapidly prototyping new algorithms, these new tools have the potential to completely revolutionize the field as we know it, leading to previously unprecedented capabilities for prediction and discovery in biology.